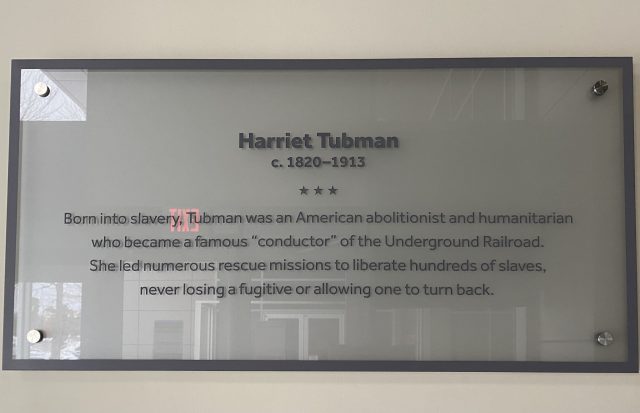

Of Stony Brook University’s 64 named buildings and spaces, only four Black historical figures — Arturo Alfonso Schomburg, Jimi Hendrix, Frederick Douglass and Harriet Tubman — are memorialized, according to a list compiled by the university’s archivist.

As sociology professor Dr. Crystal Fleming explains, Stony Brook University’s lack of Black memorialization shows a much deeper insight into racial inequality on campus.

“When we look at the underrepresentation of not just Black people but indigenous people from the highest positions of leadership and the realities of racism that many of our Black students, faculty and staff are still dealing with, it does not surprise me we don’t see more representation and inclusion of Black people in our monuments on campus,” Fleming said.

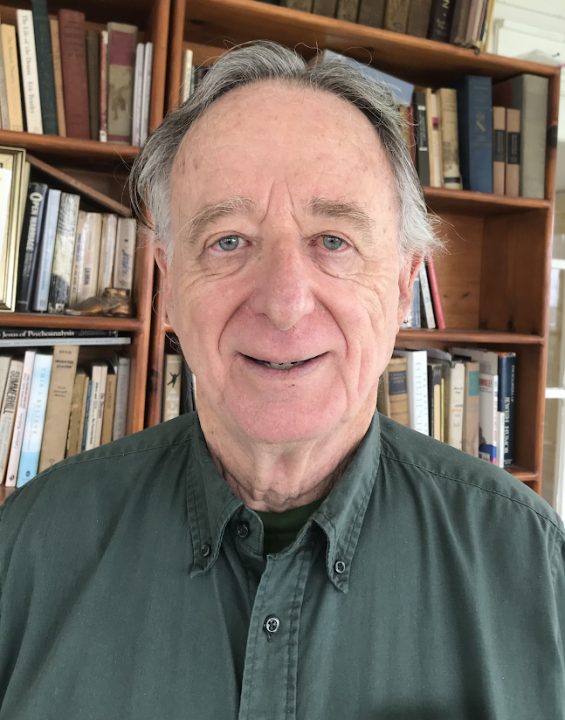

Dr. Robert Chase, an associate professor of history, expressed a very similar sentiment.

“The history of America is one where public memory is overwritten with narratives that too often valorize powerful people who were weighed over and often against [people of color],” Chase said.

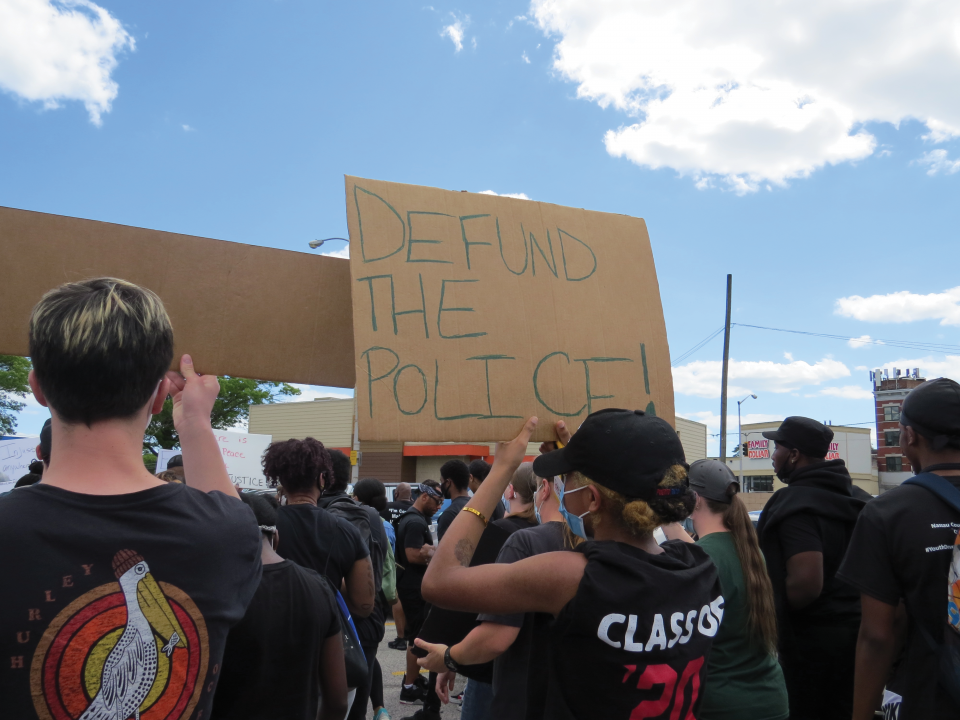

From student-led petitions to roundtable discussions, the renaming of buildings has been debated and discussed on campus since this past summer. Following the months of protests related to the Black Lives Matter movement, Stony Brook University announced in a July 21 statement the formation of the Renaming Buildings, Spaces and Structures Ad Hoc Committee.

“I think that activists have a keen grasp of history and are interested in making those connections to the present,” Chase said. “It’s only natural then that they look at the monuments of the museum, the building names and see that as a part of a greater racial inequality that affects their day-to-day lives.”

He explained that there comes a point where memorialization can only serve as a temporary solution to the greater problem of societal inequity.

Students have expressed similar thoughts.

Reimy Concepcion, a senior English major and secretary of the Black Women’s Association, explained that as a minority in such a large student body, the feelings of isolation are impossible to ignore

“I saw how [Stony Brook] took all these initiatives for these other student populations and it makes you feel like you’re drowning in the sea,” Concepcion said. “That is how I felt often — like maybe I should just transfer somewhere like in the city where I know they’re more students of my color. But I think it would really provide that recognition that [Black students] are definitely looking for.”

Concepcion expressed a desire to see Stony Brook University move toward “meaningful change,” such as a dedicated space for Black students to host events/club meetings.

“We have an LGBTQ center, and I thought that was a great idea — it gives LGBTQ students that reassurance from Stony Brook like, ‘We see you, and we hear you. We know that you have not been the most accepted by our society, but we’re here to let you know that we’re different from everyone else,’” Concepcion said.

Chase recommended that the university should look to create discussion on historical Black figures through academia.

“I would bet that most students do not know who Frederick Douglass was,” Chase said. “As a university, if we truly want to embrace a notion of broader racial equality, we ought to have a program that every incoming freshman would read one book a year; we could read something on the name of the building that we’ve designated as something to honor.”

His suggestions also included possible trips to the Schomburg Center in New York City, named after Schomburg who is considered the “Father of Black History” and was integral to the Harlem Renaissance movement.

As Fleming emphasized, names only carry so much weight.

“I’m a scholar of commemoration and collective memories so, of course, I have written about and sometimes speak about and still have an interest in questions of collective memory,” she said. “But it’s important to move beyond visual or commemorative representation and think about actual Black people.”

Citing her experience working with Black and Jewish students and groups, she said how people are treated is worth more than just representation.

“I would ask, what is the point of naming a building after an African American? What is the point? Is it only to honor the past, or is it to inspire anti-racist action? It should be the latter,” Fleming said. “It shouldn’t just be about representation and allowing a university to brand itself as diverse and inclusive, without doing the work of actually addressing how Black people, both on campus and in the broader community, are treated by the University.”