Matt Venezia is a sophomore biology major with a minor in writing.

One of my favorite subjects in high school was history. It was, and still is, fascinating to learn how we as a society got to where we are today and which events shaped us. American history was no different and my United States history course was one I always looked forward to.

Looking back now, it was very obvious from the textbooks I read or lessons I learned that “American” meant “white.”

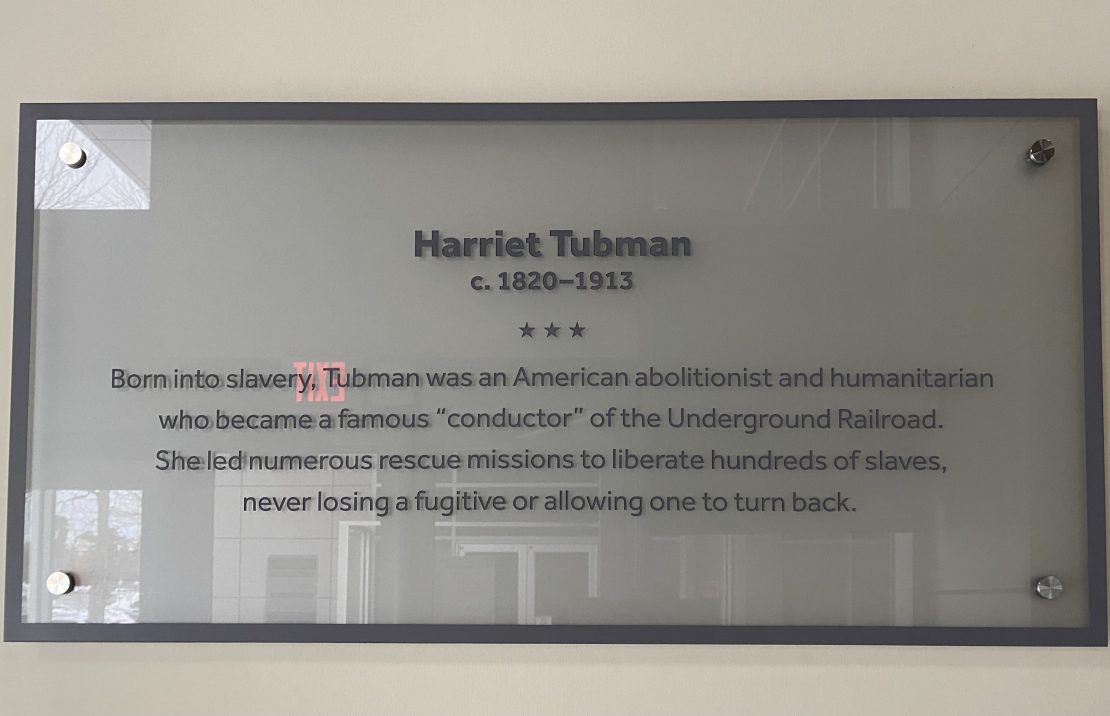

Any person who had descended from a country outside of western or northern Europe in American history had a qualifier next to their name in the textbooks. Eli Whitney was an African-American, Henry Ford was an American, Thomas Jefferson was an American, Sequoyah was a Native American and so on.

This qualification of individuals was the least offensive part of whitewashing. On the other end of the spectrum, atrocities against Black people, indigenous people, Jews and other racial and religious minorities were not treaded on by any of my teachers or taught in my textbooks. There were no substantive discussions on slavery or the desolation of indigenous lands and peoples — America’s two original sins. The enslavement of an entire group of people and the near destruction of another were not considered resulting from anything but unjust policies that, today, have no bearing on our future. They were considered merely a stain of our past.

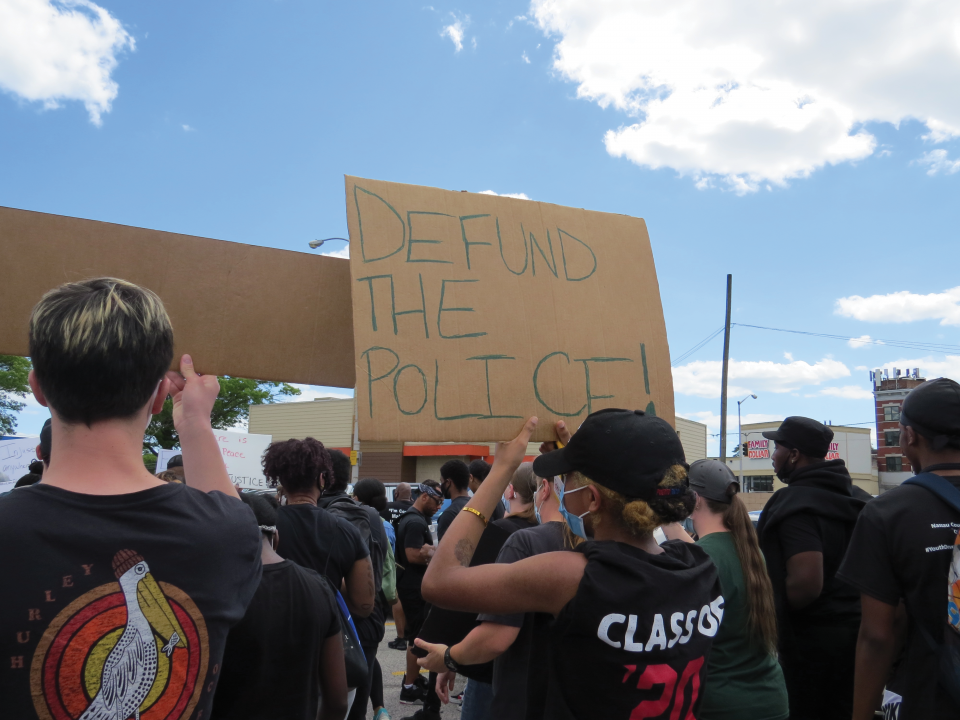

Today, we are still struggling with the damaging effects of our history. After all, it is the reason we are where we are right now. The Black Lives Matter movement has pushed people of color to the front and center of our national discourse. If we as a nation are to listen to them, our view of slavery cannot be that it was “unjust” or “wrong.” Those are the obvious statements to make. The difficulty comes in reconciling with our collective past and understanding that those stains are still affecting millions of people.

Racial tension in the United States has reached a boiling point. It’s no secret that white supremacy has been on the rise since Charlottesville in 2017. The racial underpinnings of politics today are clear.

The birther theory popularized by former president and Twitter user Donald Trump, who claimed that then-President Barack Obama was not born in America, was the center of many political movements in the years leading up to his election to the presidency.

Trump’s rhetoric throughout his time in office and the rhetoric of pundits like Laura Ingraham and Candace Owens have their basis in race. Those same racial underpinnings are evident in the Confederate flag that was flown in our Capitol during the insurrection in January, just as it is in the monuments of Robert E. Lee and other Confederate generals still standing around the United States.

These racial underpinnings manifest in policy as well. Segregation and Jim Crow laws ended less than 60 years ago. Indigenous people did not have the right to vote in every state until 1962. Residential districts were redlined, a process that made Black families less eligible for loans, until the late 1990s.

Even today, Black people are disproportionately more likely to end up in prison as opposed to every other race in the United States; one in every three Black men will end up in prison in his lifetime in the United States. These policies affect people directly, especially Black families, and have led to cycles of poverty for many Black families in the United States. These cycles of oppression also extend to indigenous reservations, where indigenous people face some of the highest levels of poverty in the United States.

The foundation for policies to replace and rectify those of the past must be built on education. Whitewashing our history will not achieve justice for all in the United States. Ensuring that young students do not talk extensively about slavery is ensuring these cycles of poverty will continue.

To break them will take an enormous national effort. But before we can take any action in the present, we have to talk about the past. Not the whitewashed version; the real American history of brutal slavery and the destruction of hundreds of indigenous cultures. We must own up our moments of national shame to break the cycles of oppression that exist today, and it all starts with a conversation in history class.