Stony Brook University’s School of Health Technology and Management hosted a panel discussing the stigmatization of mental illness in the Black community on Feb. 11.

The panel, which was held on Zoom, was part of the school’s Office of Diversity, Equity and Inclusion’s Black History Month celebration. The office chose mental health as their topic, specifically focusing on Black people’s experiences with the stigmas surrounding therapy and mental health care. Twenty-five students, staff and faculty attended the event.

The event comes during the worldwide Black Lives Matter movement, which has shined a spotlight on healthcare inequities and police brutality that Black people face daily. Through their research in 2015, The Journal of Healthcare for Poor and Underserved found that Black American men being treated for depression face treatment disparities including misdiagnosis, racism and cultural mistrust.

The panelists for the event were Deputy Director for Strategic Initiatives at the Association for Mental Health & Wellness Anne Marie Montijo, Broadhollow Psychotherapy owner and clinician Sheri-Ann Best and former Assistant Dean for Multicultural Affairs Jarvis Watson. Robbye Kinkade, the director of diversity, equity and inclusion for the School of Health Technology and Management, moderated the panel.

“As shared by our panelists, many Black folks are raised to keep feelings that may be misconstrued as weakness, to oneself for fear of being perceived as weak,” Kinkade wrote in an email to The Statesman. “In addition, there has been a longstanding and legitimate mistrust of the ‘healthcare system’ in the U.S. based on the damaging, unethical, and inequitable treatment of Blacks.”

Montijo, a licensed social worker and the deputy director for strategic initiatives at the Association for Mental Health and Wellness, brought up the lack of diversity within psychiatry and therapy. According to the American Psychiatric Association’s Center for Workforce Studies, 86% of psychologists are white. Only 4% are Black.

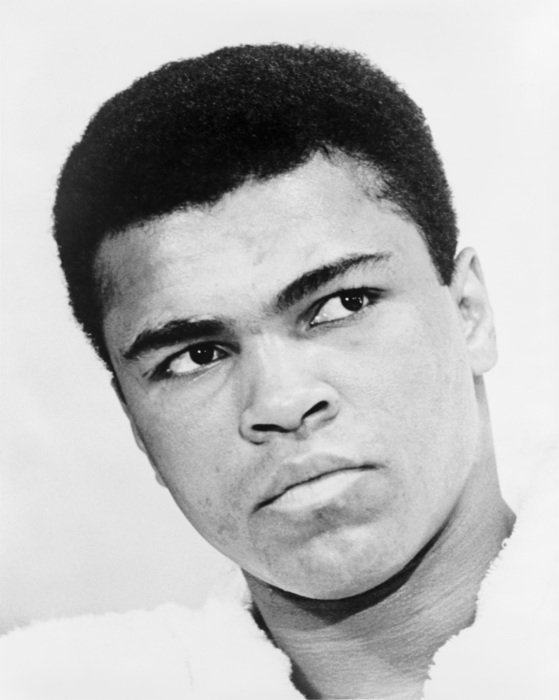

She also discussed inherent biases surrounding Black men that may affect the quality of treatment they receive from a non-Black mental healthcare worker.

“It’s long overdue that we address this issue,” Montijo said.

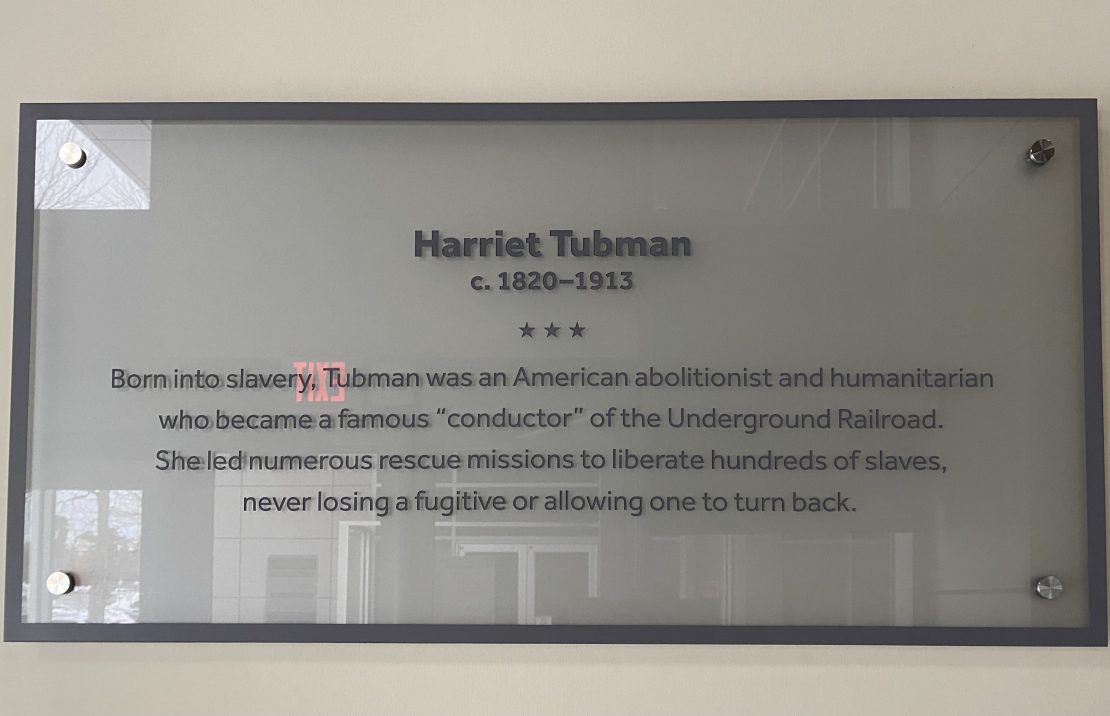

A clinician for seven years before specializing in trauma therapy, Best said that a wonderful part of her job was that she could “bring hope to the table.” She raised the topic of intergenerational trauma amongst Black people that could make them more susceptible to illnesses like anxiety and depression. Best noted that during the period of American slavery, runaway slaves were diagnosed with a mental illness called drapetomania, as an explanation for their unwillingness to be enslaved.

“Today we wonder why there’s a hesitancy for Black people to go to therapy,” Best said. Only one in three Black adults who need mental healthcare will receive it, according to the National Alliance on Mental Illness.

Black college students face specific mental health care struggles, and Watson, now the director of diversity, equity and inclusion at the School of Visual Arts, has had almost 20 years of experience advocating for marginalized students and their health. He touched on building trust with students and maintaining that relationship.

Watson said he believes that the systemic oppression of Black students in the education system and the media portraying Black youth in certain ways might discourage students from seeking help.

“You’re going to develop some sort of PTSD or trauma by thinking I’m going to get through this the best I can,” Watson said about students of color. “You’re not a machine or superhero.”

During the second part of the event, Kinkade asked the panelists several questions about the effect of microaggressions on mental health, why men in particular avoid therapy, intergenerational trauma and the myth of the “strong Black woman.”

The panelists identified all these problems as layered and complex because of systemic inequalities. In her own practice, Best recognizes that microaggressions take an everyday toll on people of color. To help her patients, Best explains to them that therapy is a process and “a place to reflect” on harmful things that happen in their lives.

In Watson’s experience as an educator, he’s identified many reasons why Black men might avoid therapy. He said many Black men fear appearing weak or needing pity, or realize that the people they want to get help from look like their oppressors, since most therapists are white. Black male role models, diverse learning environments and healthy peer relationships are all key to fixing this problem, Watson said.

Best agreed with Watson, saying that Black women also fear appearing weak and feel they need to look strong. She called it a “heavy burden” they carry every day.

“When you walk in [to therapy], hang your cape up on the door,” Best said. “You don’t need to be a superhuman here.”

In the third part of the event, panelists took questions from the audience. The Statesman asked what professors could do to help BIPOC students in the classroom, especially during potentially traumatic events like protests and political strife.

Watson said that professors should learn different types of presences within their classrooms, such as an equity presence — which means educators must explore their own culture as well as their student’s cultures. He said professors should recognize their own biases before trying to help students and take advantage of implicit bias training.

Most importantly, educators should be present, provide resources to students and in the case of referring a student to therapy, they should not just pass off students but hand them off. Professors should strive to build a bond with their students instead of only recommending them to campus mental health services, according to Watson.

“Be intrusive in a holistic way,” Watson said. “Ask how they are.”

Karen Mendelsohn, assistant dean for academic and student affairs at the School of Health Technology and Management, added that professors need to “acknowledge… in the classroom that this is what’s happening. Things that are happening in the country and world… could be affecting anyone in the classroom.”

Kinkade said she hopes attendees will walk away “with an understanding that mental illness does not have to be a source of shame,” and that like with any other physical illness, there are solutions for folks from all backgrounds. She wishes that healthcare practitioners would also realize that there are “concrete and specific” reasons that many people in the Black community will not reach out for help.

“Most importantly we hope that for any person who feels that they need help, they can ask for it without shame,” Kinkade said. “That is okay to not be okay, and equally okay to say that you are not okay.”