As a predominantly STEM school, Stony Brook University is never short on students trying to get involved in science, particularly research.

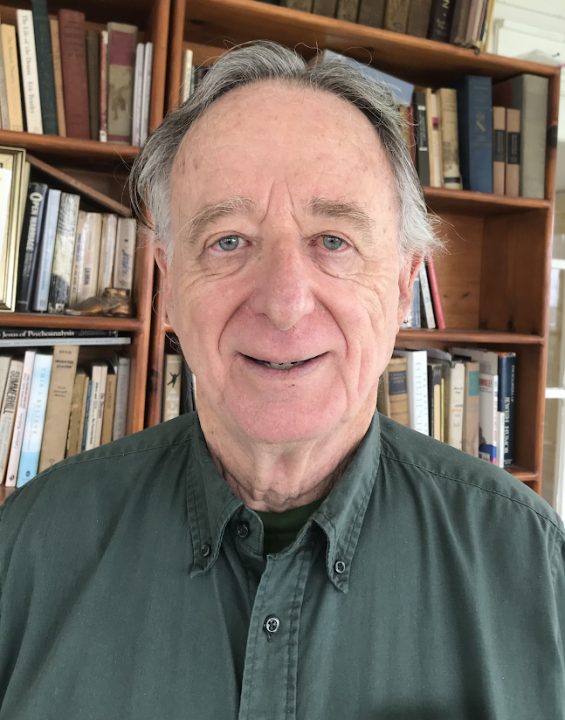

The path to finding research experience, especially without prior training, is often a difficult one for undergraduates. Eight years ago, Sharon Pochron, a primatologist-turned-ecotoxicologist and a professor and faculty director at Stony Brook, hoped to change that.

In 2015, the Sustainability Studies Earthworm Ecotoxicology Lab (worm lab) was born. This largely undergraduate-staffed ecotoxicology lab was built from the ground up by Pochron to help undergraduates get more involved in hands-on research.

“I was sitting around, going ‘what can I do? What’s dirt cheap?’ That was my thought process,” Pochron said, recalling her progression to founding the lab. “Some basic ecotoxicology was my answer, ‘How hard could worms be?’ I thought … so I started the worm lab as a club for one semester to try it out.”

After some success with the club, Pochron followed the advice of colleagues and transitioned the worm lab into a curricular, upper-division laboratory class (SUS 351/352) which students could take for credit.

“I [started] the class … thinking surely there are others doing this, which I came to find out there weren’t … We started that semester with seven undergraduate students,” Pochron said.

This semester, for the first time, the worm lab is also being offered as an SBU 102 course — a course only available only to freshmen. As a result, there are now over 30 undergraduate students in the worm lab, many of whom are freshmen, all working on ecotoxicology projects. One of the major projects involves an interdepartmental collaboration with the Department of Chemistry at Stony Brook, specifically Dr. Benjamin Hsiao’s lab.

Hsiao’s lab recently developed technology that utilizes plant waste — like corn stalks or fallen leaves — to create fertilizer and biogel, a substance that can be put on top of soil to retain moisture.

Nadege Durand is a member of Hsiao’s lab and a first-year Ph.D. student in chemistry.

“We treat biomasses, whether it be jute, plant waste, coffee groups, through a Nitro-Oxidation Procedure (NOP) which prepares carboxycellulose nanofibers,” Durand said. “This process has a variety of applications including water filtration, soil enhancement and fertilizer preparation.”

Pochron explained how they are trying to get big and small companies in agriculture to use it.

“But the main question from growers is: is it safe?” she said.

Pochron’s students are working to find an answer to that question.

“We’re looking at the fertilizer and the biogel and assessing its safety in earthworms, plants and more,” Pochron said.

Justin Weissman, a senior sustainability studies major who leads a project in the lab assessing these products’ safety in soil, explained that the project will involve exposing compost worms to the biogel and fertilizer. Then they will be put through a stress test to determine their health after the exposure.

“Worms are some of the best ecological trackers of soil health,” he said. “So it’s kind of an industry standard — figuring out the effect of a new chemical in the soil on worms.”

The lab will then send out a sample of the fertilizer and biogel to Cornell University. Weissman said this is to make sure it contains no heavy metals or toxins.

“So then, with this information and our experiment, we will be able to see if the biogel and fertilizer are safe for farmers to use,” he said.

Another project in the lab aims to efficiently sequester carbon with a fast-growing source of plant matter. Other projects are centered around investigating the impact of everyday chemicals, such as sunscreen, on organisms in the environment.

The work currently being done at the worm lab not only represents a beneficial interdepartmental collaboration but is also a testament to what can be accomplished when undergraduates are given the opportunity to participate in science outside of the classroom.

For students like Ava Green, a freshman biology major participating in research in the worm lab through SBU 102, this is the first chance at a hands-on experience in science.

“In high school, I never had a lot of research opportunities … whenever we did experiments we knew what the outcome would be,” Ava said, “but this is the first thing I’m doing where I … don’t know what the outcome will be.”

In fact, the lab itself is an experiment.

“There’s really good evidence to suggest that research experience fosters STEM belonging and helps students … stick with the hard coursework,” Pochron said. “A lot of this is funded by [the National Science Foundation] to study the impact of research experience when given to freshmen … on retention in STEM and rates of graduation.”

This research aims to show the beneficial effects of research experiences like the worm lab on the educational outcomes of students, and also to foster the creation of more places like the worm lab at Stony Brook and beyond.

Beyond the study, the worm lab has a positive impact on student growth. Pochron explained that her students learn “team building, believing in themselves, problem solving, critical thinking, and self-confidence” through the lab experience.

Darci Swenson Perger, a Ph.D. student studying environmental and marine science, currently works in the worm lab. Perger has worked with undergraduates in lecture halls and classes throughout her Ph.D. and agrees with Pochron’s sentiment.

“[The worm lab] makes me want to continue working with undergraduates, to stay in that field … I’m not sure exactly where I want to end up after I defend my thesis, but I definitely want to work with undergraduates,” Perger said.

Weissman also commented on what the worm lab brings to his education. “I think it’s interesting, because I have no need to be in this class – I don’t need the credits. The only reason I’m here is to further the worm lab’s research because it’s something I’m passionate about: the real science that gets done here.”

He said that the easiest route to join the worm lab is to sign up for SUS 351 in the fall, 352 in the spring, or volunteer during the summer. Students can take the three-credit class up to four times and conduct senior honor thesis research in the lab as well.

Weissman explained how the worm lab allows him to apply his studies to real-life scenarios.

“Sometimes students can get lost in the books and lose that passion, but this class helps keep it alive,” he said.