Maya Brown, assistant news editor, is a junior journalism major with a minor in political science.

Every time I see a blue lives matter flag wavering in the wake of a cruel Black death, my stomach begins to compress. I cannot help myself from tracing down the complicated, yet broken system that is law enforcement in this country.

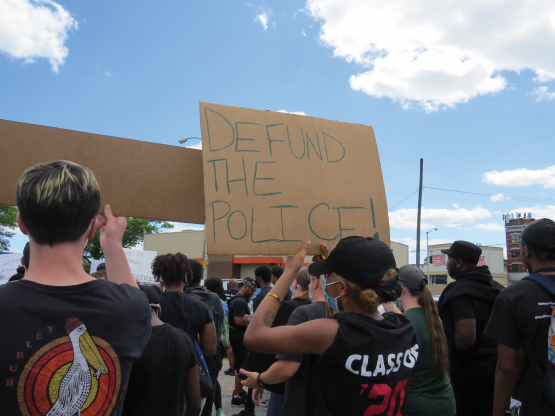

Months of increased momentum of the Black Lives Matter movement, daily protests and thousands demanding justice for George Floyd, Breonna Taylor and the long list of Black people who have been wrongfully killed, have led to many wanting the same thing — to defund the police.

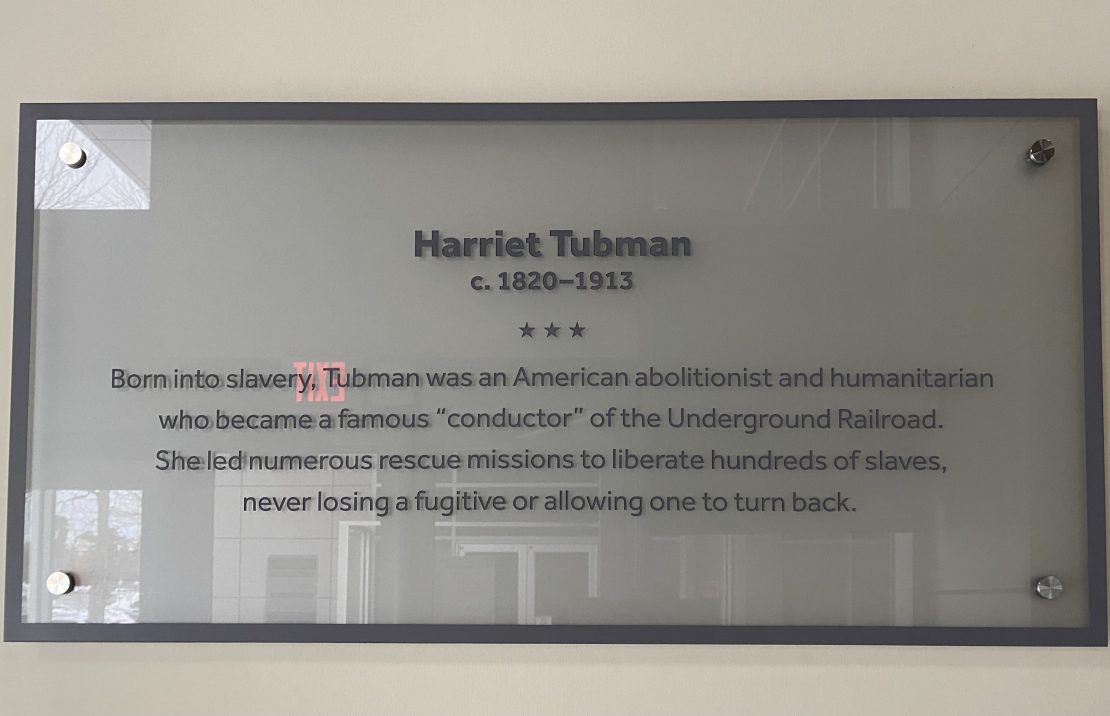

Let’s be clear about one thing: policing has never been a neutral, non-racist institution. To understand the racial injustices that bleed into law enforcement today, we must first go back to the roots of why it was created. The first U.S. city police department was a slave patrol.

In the South, specifically in the Carolina colonies back in 1704, law enforcement was tasked with chasing down enslaved people who had run away and putting an end to possible slave revolts.

After centuries of revolutionizing race relations in America, law enforcement remains a threat to Black people. The risk of being killed by police force is highest among Black men, who face about a one in 1,000 chance of being killed by police over their lifetime.

There aren’t just a “few bad apples” within the police force. It’s the system, itself. An important thing to also remember is that George Floyd was not the first. Breonna Taylor was not the first. Black individuals have been targeted and executed at the hands of police since the institution’s inception.

Even though calls for police reform have been ongoing, Black people are tired of nothing being done to address police brutality. I, as a Black person, am tired of seeing Black people die for being targeted due to the color of their skin.

Defunding the police has been a topic of controversy over the past year, and while there are varying explanations to define what it looks like, let’s not forget its common goal: Black lives matter.

Defunding the police does not mean abolishing the police department or having zero form of law enforcement. It means to, instead, reallocate funds to social services within communities across the nation.

The U.S. has one of the highest funded law enforcements in the world. Since the war on drugs under the Reagan administration, police funding has increased by more than 200% from 1980. Police budgets throughout the country range from over $100 million a year to $5 billion a year, according to a 24/7 Wall St. special report in 2020. This excessive funding is a problem because law enforcement spending should not be higher than social services, especially if the system has proven to be discriminatory.

What many forget is that the extent at which crime happens in a given community directly correlates to the number of resources that are invested into that community. Underlying conditions that contribute to crime include homelessness, poverty and poor public health. Defunding the police and prioritizing funding into social resources that truly matter, will address many societal problems and lead to a lower crime rate.

For example, if funds are taken away from a local police department, that money could instead be reallocated towards schools, social services and affordable housing. Some reasons we have youth-related crime are because of undereducation and a lack of housing for those who are most vulnerable to falling through the cracks. Readjusting county, city and state budgeting for public services to focus on supporting school counseling and housing needs would lower the crime rate and help end inequality at the source. This is an idea that is also shared by doctoral candidate Phillip McHarris and strategist Thenjiwe McHarris.

Another point I cannot stress enough is that police officers are also not always fit for their specific calls for service. In many cases involving substance abuse, domestic violence and mental health crises, police officers handle these situations even though they aren’t always professionally trained to do so. Mental health professionals, like counselors, are better equipped to deal with mental health crises, yet they are not always called to remedy these types of situations.

Last March, Daniel Prude, a Black man who was having a psychotic episode, died after Rochester police officers placed a mesh hood over his head. This case is not solely unique to Prude, however. In 2018, police shot and killed about 25% of people who were experiencing a mental health crisis.

Prude’s death is an example of why police should not serve as our first-line responders to mental health crises, as they’re not always adequately trained to deal with such situations. The harsh reality is that police brutality will remain until we implement an expansive, medically-informed mental health response. This can begin when the state first funds mental health professionals to protect and even save lives that are at risk.

The momentum of defunding the police has also brought around genuine change since last year.

Los Angeles Mayor Eric Garcetti pledged to reduce the LAPD’s almost $2 billion budget by as much as $150 million and redirect the money to health and education programs. In Boston, Mayor Marty Walsh announced $12 million from the police budget would be reallocated to social services, including programs aimed at reducing inequality in the city. Money will instead go towards violence prevention, language access, food security, immigrant advancement and other services that will foster neighborhoods.

In New York, the City Council and Mayor Bill de Blasio passed a budget last June that shifts $1 billion away from the $6 billion budget of the NYC police department.

These were steps towards the right direction, and we have to continue to defund police departments everywhere because change happens systematically. Nothing will be accomplished for Black people if only a single local police department is defunded. The country needs to reform the entire body of law enforcement and analyze if the system is doing what it is intended to do — to protect and serve.

Now that we addressed the goal of this movement, the pressing question becomes: What happens after it is brought into the national spotlight? I am tired of seeing a movement in the shape of a tsunami turn into little droplets with no momentum.

Black communities deserve better. They deserve reinvestment. Why would we continue to fund a broken system that is not working? Defunding the police is vital for America to say aloud, Black lives matter, with conviction.

Corrections 3/8/21: When the op-ed was originally published, it said that the first U.S. city police department was a slave patrol. Although slave patrol was the first form of policing in the Southern colonies, the first American police force was established in Boston in 1838.

3/16/21: An earlier version of this op-ed cited an article that stated that the police shot and killed about 25% of people who were experiencing a mental health crisis. The article actually stated that 25% of the people who were fatally shot by the police had mental illnesses.