With scientific advancements occurring at an unprecedented rate, tasks that once seemed impossible are now in arms’ reach. One of these not-so-impossible goals is recreating extinct species through genetic modification and splicing. However, just because something can be done does not mean that it should be — the last thing we need is our own live rendition of “Jurassic Park.”

Take the dino-chicken project, for instance, in which scientists are using atavism, the altering of traits in an existing being to bring back the lost genetic traits of ancestors. Scientists want to use the body parts of chickens to create a modern-day dinosaur. Paleontology curator and professor Jack Horner, who inspired the character Alan Grant from “Jurassic Park,” started the project in 2009.

Birds are all descendants of dinosaurs; they are specifically related to theropods, two-legged dinosaurs. In fact, chickens and ostriches are the closest relatives to dinosaurs, according to Bluereef Aquariums.

A 2020 National Science Review reveals that researchers have discovered actual DNA within fossilized dinosaur cartilage. However, according to Horner, it is unlikely that an entire genetically modified dinosaur can be recreated through such little DNA.

“We think we have found signals for DNA and that there might be tiny bits left, but not enough to use to make a dinosaur,” Horner explained in How It Works magazine. “We can get collagen and some dinosaur proteins, but not all the material we need.”

It sounds intriguing; scientists are at a point where a chicken can turn into a dinosaur. It proves how much progress scientists have made in the realm of genetics and paleontology. I don’t think that in the coming months the world will be overrun by dinosaurs — I just can’t wrap my head around why we have to recreate dinosaurs at all. Unlike other genetically modified species, dinosaurs would have no logical purpose to serve.

When I think of any project involving the genetic makeup of dinosaurs or trying to recreate dinosaurs for research, my mind fills with “what-ifs” that prevent me from being fully on board with the idea.

What if scientists are ill-prepared to maintain and care for a dinosaur? It must be reiterated that it seems as if the successful creation of a dinosaur is well in the future. However, if a dinosaur is successfully made, there is really no way to know what to expect.

What if this research results in something dangerous? We wouldn’t know how to properly contain or domesticate a dinosaur; it would most likely be a trial-and-error process with the errors being fatal. Granted, no one has ever successfully recreated a dinosaur; these fears are solely based on “Jurassic Park.” Genetic modification of animals has never been taken to this extreme.

With any sort of genetic engineering, there’s always the question of what the animals are being put through. One scientific journal discusses the “moral notion” behind experimenting with animals. However, when everything is said and done, scientists have motivations beyond the animals’ well being. Their projects and reputations are on the line.

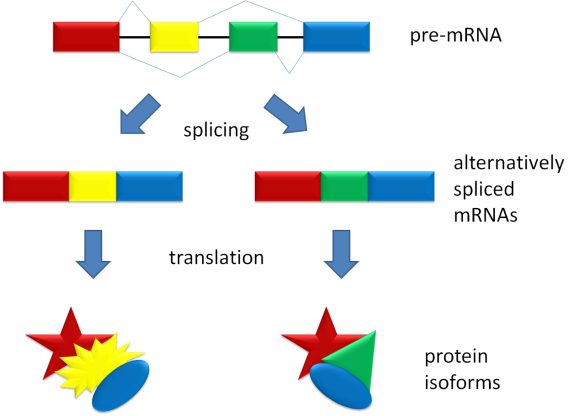

Wooly mammoths could also make a comeback with the efforts of George Church, a genetics professor at Harvard University. With 15 million dollars devoted to the project, Church is using gene splicing to revive the species.

Some researchers believe that the reintroduction of mammoths could aid the fight against climate change. According to an NPR article, mammoths used to scrape at snow, allowing air to maintain permafrost in the Arctic.

“After they disappeared, the accumulated snow, with its insulating properties, meant the permafrost began to warm, releasing greenhouse gasses, Church and others contend,” the article states.

Similar to the previously discussed dino-chicken, the new mammoth would not be identical to the original species; scientists are working with elephant genetics and DNA found from frozen mammoth remains.

Unlike the dino-chicken, there is real scientific intent that could make a serious environmental impact. However, I don’t think that this plan will play out well. Introducing a new species into an ecosystem may actually cause more destruction than maintaining it.

I don’t think that relying on a genetically modified elephant-mammoth combination to dig us out of the climate crisis is the most realistic course of action. It’s awfully ambitious when there is so much uncertainty in the result.

There are a million ways to spin and question the ethics, practicality and necessity of recreating extinct species. Such a project is not worth the risk and uncertainty of the outcome.