Stony Brook University researchers in psychology and computer science have received a $2.5 million grant from the National Institutes of Health (NIH) to fund the development of potential new treatments for addiction that could intervene before a person at risk has a relapse.

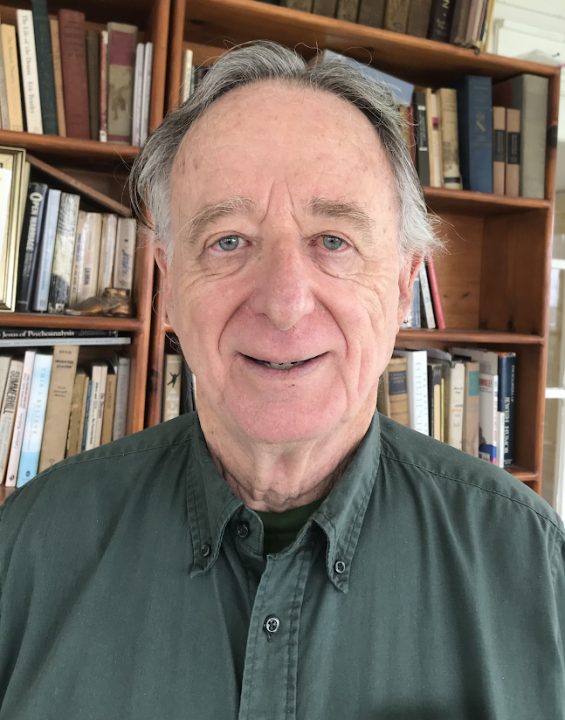

The study, in collaboration with professors from the University of Pennsylvania, is led by H. Andrew Schwartz, assistant professor of computer science at Stony Brook University. Schwartz’s team is trying to develop an artificial intelligence (AI) program that can scan social media data and use the recorded information to understand the users’ habits in order to predict their future behavior. In this case, the team is focusing on the ability to understand how mood and environment lead to unhealthy drinking behavior. Such behavior is defined as 14 drinks in a single week for a man, or seven drinks for a woman.

The subjects of this study will be bartenders and restaurant servers, who were ranked third out of 19 industries in the U.S. for reported heavy alcohol use. To help test the effectiveness of the predictions, the social media data will be compared against data from an intake questionnaire and data from specific subjects who will answer questions from the app around six times a week for 28 days about their emotional state.

One organization that is willing to use the results of this study in their own work is the Long Island Council on Alcohol and Drug Dependence (LICADD), a 65-year-old community outreach organization that helps connect Long Islanders suffering from addictions to treatment. Sometimes, treatment is entirely in-house, such as LICADD’s relapse prevention support groups and counseling for families and friends who are attempting to stage successful interventions. The organization frequently refers people to the proper treatment facilities on Long Island.

“One of the things that we sometimes see lagging in treatment of addictions is the use of [AI] technology,” Adam Birkenstock, a licensed clinical social worker and director of programming for the LICADD, said. “If there was an app available for clients to be able to track their own … possible risks for relapse, I do think people would be responsive to it.”

According to Birkenstock, LICADD has long used digital technology in their work. The organization runs a 24/7 hotline to help people find treatment facilities on Long Island, and heavily depended on teleconferencing services for homebound clients even before the COVID-19 pandemic began. LICADD has yet to use more cutting-edge technology, such as AI.

Schwartz’s study is still in its early stages. Work began in June 2020 and the grant is slated to be awarded in installments over the next four years. The current study is based on a prior study co-authored by Schwartz and a team from the University of Pennsylvania, which demonstrated that Twitter language data can capture patterns of unhealthy drinking and predict their rates. The prior study also showed that the patterns match with the Center for Disease Control and Prevention’s Behavioral Risk Factor Surveillance System telephone survey data from 2006 to 2012.

Schwartz sees two potential ways that the models can be adapted into technology.

One direction could be a self-help app in support of traditional therapies. The patient would let the app analyze their social media data and would report what their social media historically looks like before, and after they experienced a night of heavy drinking. The app could give a patient an early warning sign of a potential relapse while also reminding the patient of the consequences of unhealthy drinking.

A second use could be a program that uses the language data from social media and texts to create new patient data charts for therapists, letting them track their patients’ stress and life difficulties in real time. The therapist would receive this data in chart form without seeing any of the text messages or posts themselves.

“Social media is not perfect,” Schwartz said. “But it gives you a window into how people’s daily lives are progressing, at least for those who are using it on a regular basis.”

Companies trying to use AI to predict and control behavior based on social media posts is nothing new. According to an article from the Washington Post, Facebook uses data gathered from multiple sites, including “ethnic affinity,” “household composition” and whether you are an early or late user of new technologies. This technology earned Facebook $69.66 billion dollars in ad revenue in 2019 alone.

Schwartz is insistent that the data used by his team would be securely transferred from consenting study participants only, who will be paid $15 for six months of their social media posting data. There are no plans to distribute the data or the models generated to commercial entities.

However, Stony Brook University students who were asked about the project had the existing uses of data-gathering AI in mind when they were asked for their opinions on the study, and their own comfort level with sharing social media data with a medical professional.

Some students were ambivalent about the idea of therapists and health researchers looking through their social media records.

“I feel like I should be uncomfortable about it,” Sean Yang, a junior computer science major said. “But I feel like we’re all kind of used to it.”

Other students had minimal reservations about sharing social media data with a personal therapist, but they noted issues on how their mood might be judged through their social media.

“It’s not a reflection of my life at the moment,” Julia Khinchin, a freshman biology major, said about her social media. She mostly posts pictures, often around two weeks after she took them. She doesn’t feel that computers are good enough at finding visual signs of disease, and therefore is skeptical about AI in medicine.

“Computers are more prone to mistakes because they are not there [with the patient],” Elana Kline, a freshman health sciences major, said.

Some students, like Yang and Christopher Wadolowski, a senior multidisciplinary studies major in theater, music and creative writing, claim to be fairly open and honest with their feelings on social media. Neither of them, however, were comfortable with sharing their social media with their therapist.

“I would have told them that [information] in the first place,” Wadolowski said. “I don’t want them snooping.”

Bars Near Me • Oct 12, 2020 at 12:17 am

Thanks for the terrific information for us.

Best regards,

Demir Hessellund