Justin Chassin is a senior computer science and applied math and statistics dual major.

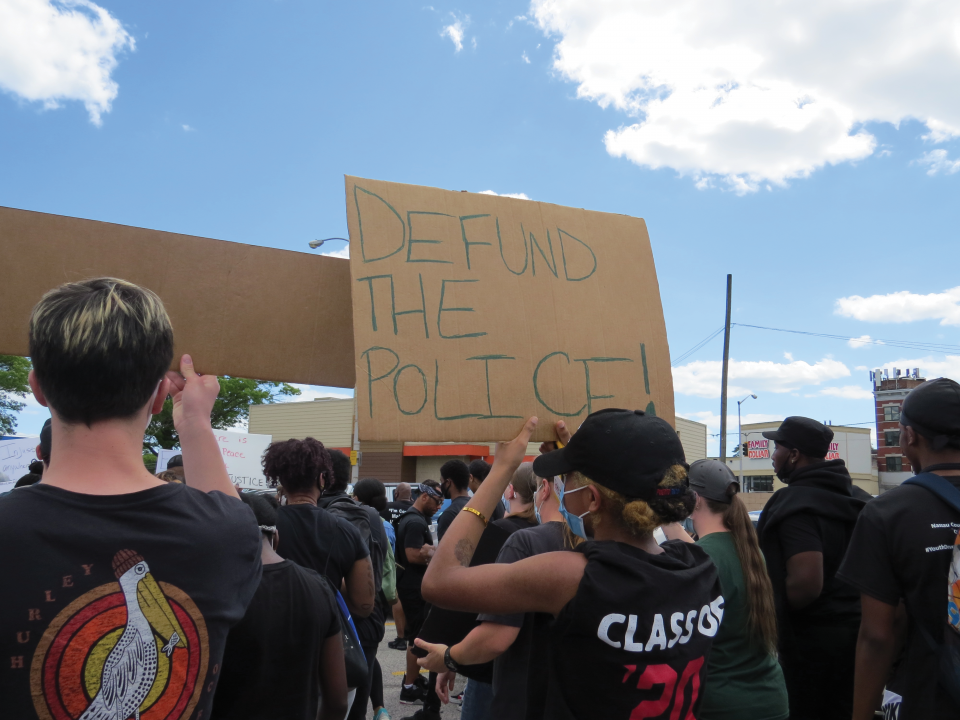

In conversations with friends and family about racial inequality over the past year, one thing I noticed was a resistance to understanding the pain of Black Americans and the reason behind protesting for justice.

Arguments that start with, “But what about Black on Black crime?” or “But police officers need to have these powers,” have been said far too frequently.

What isn’t talked about is qualified immunity, a law that protects police officers from legal accountability for crimes so long as it does not violate clearly established statutory or constitutional rights. This is a law with a track record of crimes rooted in racial biases that have been weaponized against marginalized groups while allowing police officers to get away with zero accountability.

Discussions therefore miss this question: “What does it feel like to grow up knowing that the criminal justice system is not on your side?”

When this perspective is not addressed, it makes it difficult to be effective allies to those experiencing discrimination.

To put it simply, an allyship is when someone from outside a marginalized group advocates for those in that group at both the interpersonal and intrapersonal level. A key feature of being an ally is to use your voice and privilege to support marginalized groups both socially and politically.

When we break it down, productive allyship is a continuous process of three qualities: perspective, learning and action.

There are certain perspectives you will never completely grasp because they lack firsthand experience. If you are not a member of these marginalized groups, they can never fully understand the day-to-day struggles they face.

In a way, allies should be like students who attempt to listen closely and ask questions to expand their understanding of those experiences.

Since one of the key components of allyship is to listen, acknowledging that you are not an expert or spokesperson for conveying the Black American experience is crucial. But how the mic is passed is just as important. To make sure that people don’t have to relive traumatic moments, you should independently seek sources themselves. Books, podcasts and articles can help you gain insight into race relations without forcing someone else to retell their experiences.

For an ally to effectively listen, they also must actively reflect on and confront their own biases that can paint how they view stories before they are even told.

When you read or hear about someone’s story, think about your own thought process. Ask yourself why you feel a certain way. If this surprises you, ask yourself, again, why? Is it because you have never experienced this or perhaps haven’t heard about it before? Critically questioning what you know and don’t know grows not only your self-consciousness but also awareness for other peoples’ experiences.

This involves facing an uncomfortable truth — unconscious biases may hurt people without you even realizing it.

Comments such as “you are just playing the race card” are mechanisms that not only divert discomfort about race, but defend biases that manifest in dangerous ways.

Stereotypes that portray Black men as “dangerous” are what got two Black men arrested for simply being at a Starbucks.

These internalized stereotypes can cause people to cross the street because they fear a harmless group and even worse, cause the death of George Floyd and countless others whose wrongful deaths are even debated.

We have to confront our prejudices, no matter how uncomfortable they are. In taking action, we need to think about why we are going to create a certain impact and how it could affect people in turn.

When intent to help is self-motivated to increase “social capital,” “performative allyship” can not only fall flat but be harmful. The nature of this usually involves minimum surface-level efforts to “check-off” a box and an inconsideration for the impact they have on movements and individuals.

An example of this was Blackout Tuesday. While people were trying to show signs of solidarity, feeds became filled with black squares that took away a platform from helpful, educational resources.

Productive and authentic allyship requires a careful cycle of understanding your own perspective and biases, learning and taking action. Throughout the process, it is key to remember that the spotlight and attention should not only be on the ally themselves, but on how they can understand the issues, attempt to transfer power and challenge biases.