“What is your nationality?”

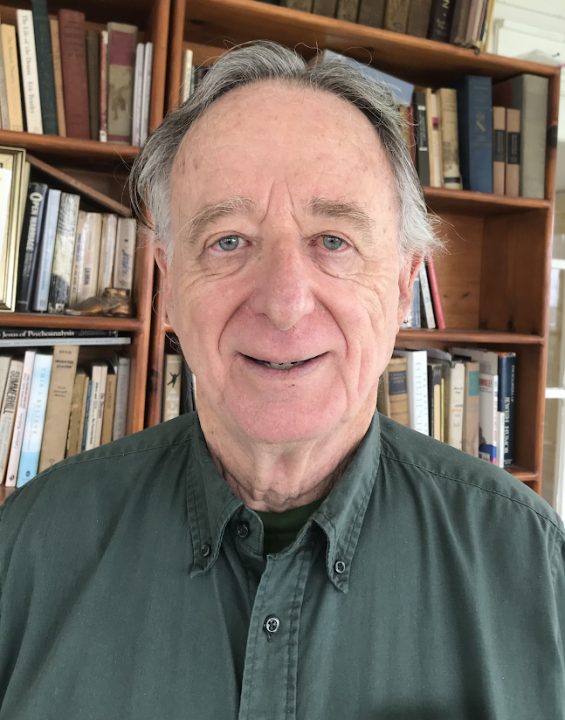

That’s a question many multiracial Americans hear, but as Dr. Zebulon Miletsky, an assistant professor of Africana Studies can attest — the answer isn’t always easy.

Miletsky, who identifies as half-Jewish and half-black, hosted a lecture called “Interracialism: Biracials Learning About African American Culture” to tackle the storied history of what it means to be African American and biracial, on Feb.19 in the Frank Melville Jr. Memorial Library’s Central Reading Room.

Key to his lecture was the “one-drop rule,” the idea that having even a drop of African ancestry renders someone “black.” Miletsky said that for much of American history, this rule was used to denigrate African Americans as a separate and “inferior species” from whites after the Civil War.

Between 1850 and 1920 — with the exception of the 1900 federal census — the U.S. census listed “M” or “Mu” for “mulatto” as an ethnicity, referring to those of both European and African descent. Prior to that, the census categorized people as free whites, all other free persons or slaves.

But by the 1930s, the “one drop rule” was applied again, rendering every biracial of African descent, no matter the color of their skin or eyes, “black.” Forty-one states at one point banned interracial marriage. Eleven lifted the laws in 1887 or sooner and 14 repealed their laws between 1948 and 1967. Sixteen states ultimately saw their laws overturned in 1967 after the Supreme Court ruled in Loving v. Virginia that laws against interracial marriage were unconstitutional.

Because of discriminatory laws like these, many biracial Americans with paler skin tried to pass as white and suppressed their black culture to dodge hatred. Some went so far as to bleach their own skin — even now, skin-lightening is a multi-billion dollar industry. Miletsky said that to this “generation mix,” any identity was better than the “dreaded curse of blackness.”

Miletsky referenced scholars like Jared Sexton, a professor of African American Studies at UC Irvine, who argues that multiracialism is a social construct that is inherently “antiblack” in all of its incarnations.

For this reason, the NAACP lobbied against the addition of a “multiracial” option on the year 2000 U.S. census out of fear that the designation would be used to splinter support for African American communities. This is the reason why the 2000 and 2010 editions of the U.S. census allow Americans to check off multiple races rather than giving them a separate option for biracialism.

Much of the media coverage of multiraciality since then has treated it as a recent event, but the notion of it in American culture goes all the way back to the Founding Fathers, Miletsky said.

Both Thomas Jefferson and Benjamin Franklin expressed joy at the thought of “the mixing of the “lovely white and red,” referring to the biracial children of Native Americans and Americans of European descent even as mulattos continued to be frowned upon as Negroes. This favoring of some races over others is what Miletsky referred to as “honorary whiteness.”

Dreams of a “post-racial America” arose after Barack Obama, the first biracial U.S. president, was elected in 2008. But according to Miletsky, Obama “rejected” the notion of being biracial in favor of emphasizing his blackness, dashing those hopes. Even today, Dr. Miletsky notes that white culture is more favored than black culture in pop culture and mass media.

“There’s nothing that speaks to me, that says blackness is valid, proud or something to behold and tell to be beautiful,” Miletsky said in outrage at the comparative lack of black representation in American standards of beauty and culture. “You heard it okay. I heard black is beautiful, but do you believe it?”

The confusion regarding biraciality and the “racial denial” of blackness that often comes with it inspired Miletsky to start the Biracials Learning African-American Culture (B.L.A.A.C.) blog, which encourages biracial African Americans to embrace black culture.

The blog includes examples of little-known biracial people such as Alexander Pushkin, the father of modern Russian literature. Miletsky also showcased Walter F. White, the president of the NAACP from 1931 to 1955, who was often mistaken for a purely white man — something he used to help investigate lynchings.

Miletsky hopes to start hosting workshops and launch a curriculum to promote black culture to the general public.

“Give some of our experts and master teachers a chance to challenge your previously held assumptions about race and whiteness in America, and the true nature of American history,” he said.

Miletsky’s lecture drew a sizable crowd, including students, staff and people outside of the university.

“I wanted to hear what he had to say,” said Hermann Mazard, the son of a Stony Brook graduate and a friend of Miletsky. According to Mazard, a Haitian American, he’s called “blan” or “white” in Haiti because he lives in America and has numerous multiracial relatives.

“I want to claim the Haitian part of my heritage,” he said. “I think it’s part of my identity.”

Other attendees thought about what Miletsky’s work could mean for biracial African Americans today.

“What he was saying is all amazing research,” Arlene Jennings, an advancement worker at Stony Brook University, said. She attended the lecture after reading about it in a newsletter. “It’s interesting to hear how this is impacting the younger generations. I think what he’s doing is awesome.”

Miletsky capped off his lecture by encouraging everyone to learn and understand black culture to end the stigmatization of African Americans.

“It’s kind of like learning a second language,” he said. “It’s never too late to learn.”