A sharply divided presidential bioethics panel issued a report in which a majorityof the members voted in favor of a four-year moratorium on attempts to createcloned cells for medical research, putting the majority-rules decision of thepanel at odds with President Bush.

Ten members of the President’#146;s Council on Bioethics argued that a moratoriumwould allow time to study moral and scientific controversies surrounding theprocedure and to improve regulatory oversight. Seven members dissented, arguingthat a delay would block the development of important medical therapies.

The seven dissenters generally said that the research should proceed only understrict regulation. In addition,there were some panel members that criticizedthe majority’#146;s position.

The panel members delivered the report after seemingly months of contentiousdebate among lawmakers and the public about the ethics of cloning, and afterthe Senate had reached an impasse on the issue.

Lawmakers on both sides of the debate failed last month to muster the votesneeded to overcome procedural roadblocks to votes on two competing bills.

One bill would allow the cloning of cells for research purposes, and the otherwould ban it. (The House of Representatives voted last year to ban researchcloning outright).

The panel majority’#146;s position is at odds with that of President Bush,who has strongly supported a permanent ban on research cloning.

Seven of the 10 panel members who endorsed a moratorium actually favored apermanent ban on research cloning, but went along with the moratorium as a compromiseposition.

Leon R. Kass, the panel’#146;s chairman and a supporter of the proposed moratorium,said he hoped the council’#146;s report would help break the impasse in theSenate over research cloning.

Cloning cells, both for reproduction and research, is now legal. But the Senate’#146;simpasse has raised questions about whether lawmakers might act later to shutdown any studies.

Mr. Bush formally appointed the council in January and assigned it as one ofits first tasks to debate and report on the ethical issues surrounding cloning.

One of the panel members, Michael S. Gazzaniga, the director of the Centerfor Cognitive Neuroscience at Dartmouth College, recently said in a statementincluded in the report that he was ‘surprised’ that President Bushhad announced ‘fully formed’ opinions before the panel had gottenthe chance to make the completed the report.

Dr. Kass, a professor of social thought at the University of Chicago, had saidthat it would be wrong for the panel to rush to complete a report. He said hepreferred to produce a thorough, well-reasoned document that would help shapewhat is anticipated to be a continuing debate about the ethics accompanying’cloning.’

The panel’#146;s majority described cloned human cells as ‘nascent humanlife.’ A moratorium, the majority said, would allow for a broader publicdebate about their moral status.

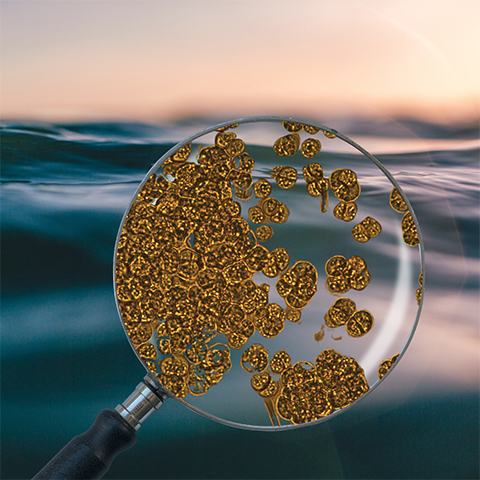

Like human embryos, cloned cells may have the potential to become a normalhuman baby. Scientists propose to destroy cloned cells to yield undifferentiatedstem cells, which they hope to grow into replacement tissue for a variety ofdiseased and damaged organs.

The report questions the ethics of creating cloned cells solely for medicalexperiments and therapies. ‘There’#146;s an important moral boundary here,and we need time to discuss the costs of crossing it and not crossing it,’Dr. Kass said.

In a letter to Mr. Bush, Dr. Kass reasoned that cloning cells represented ‘thefirst step toward genetic control over the next generation.’

The report suggests that allowing cloning would lead scientists to manipulatethe genes of developing embryos to create desirable traits in the resultingbabies. ‘Cloning represents a turning point in human history … and carrieswith it a number of troubling consequences for children, family, and society,’Dr. Kass wrote.

The panelists also split over the scientific controversy surrounding clonedcells. Members of the majority said that a moratorium would allow researcherssubstantial time to conduct further experiments using adult and embryonic humanstem cells.

This could allow them to discover if the cells could be manipulated to achievethe same medical therapies that scientists hope to achieve using stem cellscreated through cloning.

However, Dr. Rowley noted that existing government policies restrict federallyfinanced scientists to studying a limited number of embryonic-stem-cell colonies.These restrictions have prevented scientists from understanding more about howstem cells work.

The government should lift the restrictions but also increase safeguards toensure that such research is conducted ethically and safely, she said, adding,’There’#146;s been very little discussion [by the panel] about the moralrights of humanity and the potential benefits of this science.’