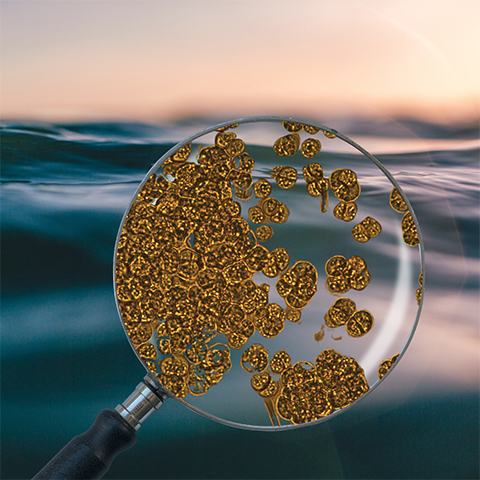

Stony Brook associate professors Jackie Collier of the Marine and Atmospheric Sciences department and Joshua Rest of the Ecology and Evolution department led an initiative to study the genome structure of the marine protist Aurantiochytrium limacinum, a type of eukaryotic cell.

Their research focused on an analysis of DNA and RNA found within an organism’s genetic material. Ultimately, they discovered that parts of the protist’s genome mimicked that of mirusviruses. More specifically, they found that the protist’s genome had the sequencing of RNA genes in its chromosomes, matching the current understanding of the mirusvirus.

Marine life sciences differ significantly from human anatomy and microbiology, which include the study of eukaryotic organisms. One example is the limited understanding of viruses. Marine environments are so diverse that most viruses do not carry the same genes, which can complicate researching viral manipulation in marine ecosystems.

Since there are a plethora of marine virus types, DNA research on marine viruses helps scientists develop better understandings of this unexplored subject. This is especially important because new groups of viruses continue to be discovered, such as the mirusviruses.

“Mirusviruses are a newly discovered group of large double-stranded DNA viruses that are strange because they mix together genes previously found in the two different major groups of viruses,” Collier said in an interview with The Statesman. “Mirusviruses appear to be abundant in the ocean, but the [current research] couldn’t identify exactly what organisms they infect. [T]hey are identified only by sequencing DNA from the ocean, not as actual viral particles infecting a host cell.”

According to a quote from Collier in Stony Brook News, research suggests that “‘A. limacinum is probably a natural host of mirusviruses and that a single host has been infected by multiple distinct viruses.’ By completing the entire genome of the protist, the researchers identified the first known host for mirusviruses, and their observations suggest dynamic host-virus genome interactions.”

This further establishes the necessity of research into the evolution, capabilities and future evolution of marine viruses, such as the “‘growing evidence pointing toward mirusviruses’ significant influence in marine ecosystems.’”

Collier and Rest’s full research publication addresses host potential for mirusviruses; this implies the groundbreaking discovery of a host being able to wield multiple viruses, and thus the possibility of hosts and mirusviruses being able to create new viruses. The information that a “first known host for mirusviruses suggests dynamic host-virus genome interactions” is highlighted on their website.

“This discovery allowed the first host of mirusviruses to be identified,” Collier said. “This will help us begin to understand this new, very abundant group of marine viruses and the role they play in the oceans.”

When discussing other potential uses for this discovery, Collier addressed the uncertainties they faced. These includes finding similarities for A. limacinum, “which seems to contain two latent viruses might give us insight into (distantly) related herpesviruses that establish latent infections in humans (and other animals).”

Collier shared that further research may see if they “can get putative mirusvirus genomes to produce actual mirusvirus viral particles by stressing the host [A. limacinum] in various ways.”

In other words, Collier revealed over email that she and her team are attempting to make the host A. limacinum exhibit symptoms of illness or death so that the virus won’t “quietly hitch a ride in its host’s genome [what it normally does], but begin to actively produce viral particles.”

“If we can do that, we’ll have isolated the first mirusvirus viral particles, and that will be a major step forward in understanding this new group of viruses,” Collier said.