This review contains spoilers.

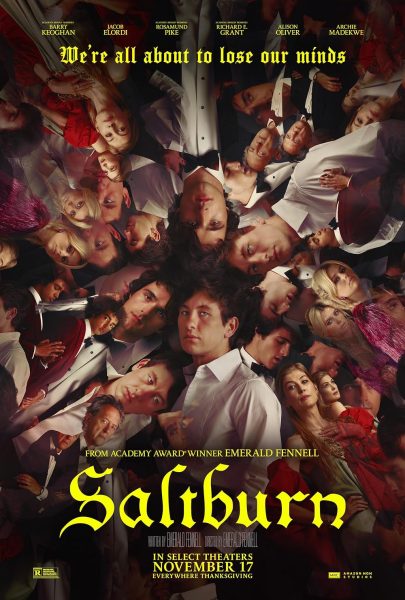

Class critiques are a defining subject matter of modern-day adult cinema. “Parasite” (2019) won the Academy Award for Best Picture, while “Glass Onion” (2022), “Triangle of Sadness” (2022) and “The Menu” (2022) made splashes in both critic and audience spaces alike last year. This year, however, America’s big “eat the rich” film comes from Oscar-winning director and screenwriter Emerald Fennell, and like her feature debut “Promising Young Woman” (2020), the subversion in “Saltburn” is as misguided as it is purposeless.

However, don’t be mistaken: Fennell is a talented, ambitious director with the necessary boldness to break Hollywood’s unfortunate trend of formulaic moviemaking. Collaborating with cinematographer Linus Sandgren, who spearheaded the visually sprawling “La La Land” (2016), “Babylon” (2022) and “No Time to Die” (2021), this director-cinematographer duo holds nothing back with “Saltburn.” The film experiments with off-kilter compositions, using warm, saturated frames resembling drug-infused eye candy.

But the audiovisual experience isn’t the problem here; rather, it’s the screenplay and writing choices that continue to baffle me weeks after watching.

Set in 2006, the film begins with Oliver Quick, played by Barry Keoghan, struggling to adapt to life at Oxford University as a scholarship student. The narrative immediately establishes an arising psychological conflict, with Oliver’s perceived lower-class background clashing with the personalities and luxuries of upper-class students. He hates the naïveté and privilege of the school’s more affluent students but craves their lifestyles and social statuses.

These conflicting feelings are magnified when he befriends the charmingly wealthy Felix Catton, played by Jacob Elordi, who eventually invites Oliver to spend the summer at his family’s estate in Saltburn — despite their friendship being marked by ups and downs and plagued with numerous disagreements. From there, chaos ensues.

Fennell is a very “literal” screenwriter, unapologetically blunt and on the nose with her use of literary symbols and motifs. The film’s sledgehammer messaging is most overt when Elsbeth, Felix’s mother, played by the brilliant Rosamund Pike, talks about the 1995 song “Common People” by English Britpop band “Pulp.” The song, a dense, lyrical examination of a relationship in which a wealthy woman craves the aesthetic of the “common person” without facing its downsides, cleverly serves as a comedic punchline while effectively portraying Elsbeth as someone who’s both out-of-touch and enamored by Oliver’s background.

Had the movie fully embraced its satirical roots, akin to last year’s “Triangle of Sadness,” the pronounced mockery of the wealthy would’ve served itself well. But, on top of being a very “literal” screenwriter, Fennell wants to be a “provocative” filmmaker — someone who wants to shock an audience with scenes of her movie circulating social media for months on end. In the end, Fennell’s provocation overwhelms her abilities as a storyteller.

Provocation generally means subverting established tropes and twisting narratives to evoke something new. But subversion can’t afford to be reckless, or else you’ll get something to the likes of “Promising Young Woman.” The story follows a woman who sacrifices herself to overcome the toxic culture surrounding sexual assault and paradoxically relies on the same uncaring justice system that led her friend to be neglected and driven to suicide. “Saltburn,” unfortunately, follows the same path, as Oliver becomes an anti-hero — the personification of a charlatan — orchestrating the demise of Felix’s family through deceit and seduction.

Not that there’s anything inherently wrong with Oliver being an anti-hero, but his motive of eradicating Felix’s family, provided the context, makes no sense. None of Oliver’s relationships with the other family members are developed enough to justify his act of killing. Moreover, there’s no charm to Oliver’s deceit. His exterior is as plain as a white T-shirt, never using his supposed lower-class allure to his advantage — while his perverse interior is hidden — making the Cattons’ head-over-heels interest in Oliver confusingly improbable.

If Felix is the object of Oliver’s desire, as implied through constant concupiscence, Oliver’s scheme to replace Felix as part of the family — by poisoning Felix — should’ve been the logical resolution. However, after killing Felix, Oliver takes another stride in his quest for vengeance, but the motives aren’t as concrete, and the experience isn’t as rewarding. The twist attempts to add ambiguity to a black-and-white story but spills a large bucket of black paint that covers the whole canvas instead.

At a certain point, the shock value of these twists and turns muddles the coherence of the narrative and gives a misguided impression of the topics it covers. When examined through a wider lens, “Saltburn” implies that the desire for wealth and status is more dangerous than those who possess it. Unless Fennell is trying to replicate the cynical works of screenwriter Paul Schrader — by portraying a complete lack of faith in the human condition — it is likely that this implied messaging was not her intention. Then again, that would be easier to forgive if Fennell’s works weren’t socially conscious. However, they are, and it’s almost impossible not to acknowledge these thematics because they are the backbone of her filmography.

The frustration serves as a deal-breaker, arguably problematic if you want to take it that far, but a part of me remains conflicted. Despite its flaws, I’d be lying if I said “Saltburn” wasn’t an exhilarating ride. Oliver, as perplexing as he is, reminds me of Keoghan’s role as Martin from “The Killing of a Sacred Deer” (2017): someone who’s unexplainably sociopathic yet oddly intriguing because of his unhinged attitude. Elordi’s Felix is endlessly charming, inversely reminiscent of Pier Paolo Pasolini’s “Teorema” (1968). “Saltburn” also plays as a dazzling millennial-themed spectacle, playing hit songs by “Arcade Fire,” “Bloc Party,” “The Killers” and “MGMT,” with a jaw-dropping needle-drop from Sophie Ellis-Bextor’s “Murder on the Dancefloor” being the cherry on top.

That scene in particular has Oliver dancing nude across the entirety of the Cattons’ Saltburn estate, fully realizing the provocation Fennell wanted to achieve; it’s a cheeky victory lap by both the character and director, allowing the audience to process the clinical insanity of the film’s content. When viewed from this lens, a question emerges: is there anything wrong with having fun?

In the end, Fennell’s work is supposed to be entertaining. She is first and foremost “from the mind of the twisted director,” and socially conscious second. Overall, I think “Saltburn” achieves the former very well.