Contains spoilers for the documentary film “Brandy Hellville & the Cult of Fast Fashion” (2024).

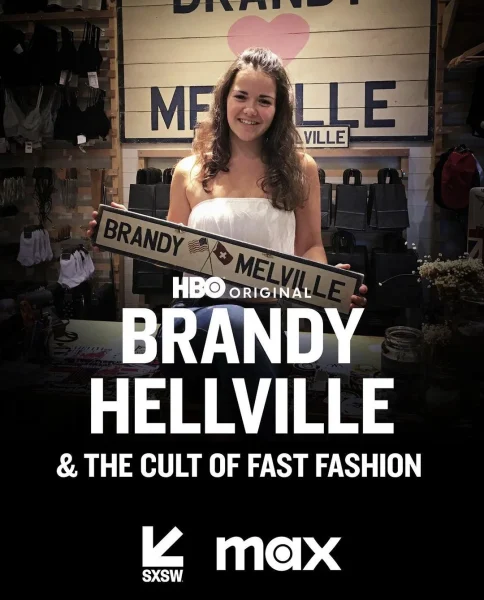

With the popularity of some of the world’s largest fast fashion brands like SHEIN, Zara and H&M, one might wonder why Brandy Melville is the spotlight of HBO’s original documentary film “Brandy Hellville & the Cult of Fast Fashion,” which was released on the streaming service on April 9. The documentary goes beyond the beach-loving aesthetic of the retailer, instead diving into the 2021 Insider article investigation on the brand’s private Chief Executive Officer (CEO) Stephan Marsan.

From clothing production processes and testimonies from former Brandy Melville employees to fast fashion’s clothing waste issues, the documentary assesses multiple problematic aspects of Brandy Melville. Although the revelations are detestable, none of them are new. Rather, it’s an age-old tale of how the fashion industry often exploits women.

The Italian clothing brand Brandy Melville, known for its feminine, Americana aesthetic also became notorious for its controversial “one size fits all” sizing approach. Likewise, its Instagram account features a consistent aesthetic characterized by attractive, skinny, white teenage girls.

Although it may seem like those who fit this image benefited from the exclusiveness of Brandy Melville, former store employees in the documentary cited struggles with eating disorders propelled by the desire to fit into Brandy Melville’s clothing. One of the former employees who spoke and was only referred to by her first name was Lee, who realized as she was overcoming her eating disorder and gaining weight that “if I kept being healthy, I wouldn’t be able to follow company policy and keep wearing their clothes. So that wasn’t good for my brain.”

The former employees also recalled coming in for work and taking full-body photos every day which were sent to Marsan, who runs the Instagram account. This unusual culture that included spontaneous photoshoots made the store employees feel like they were part of an exclusive club — at least the girls who worked in the front who were almost always white.

According to Kali, a former stockroom employee, the white employees never worked in the stockroom because “if you were white, you had to be in sight.” The blatantly racist workplace wasn’t coincidental as Marsan told store managers to fire employees he deemed unattractive and would even close stores if he felt they attracted too many minority customers.

Brandy Melville isn’t the only retailer to foster this toxic workplace culture. In 2004, Abercrombie & Fitch settled a bias case for $40 million, brought forward by minority and female plaintiffs who reported similar exclusionary instances of discrimination during the job hiring process and being assigned back-of-the-store jobs.

Marsan’s mentality parallels that of the former Abercrombie & Fitch CEO Mike Jeffries, who selected the employees based on appearance to appeal to specific customer demographics. Jeffries never hid his intent, saying in a 2006 interview with Salon, “we want to market to cool, good-looking people. We don’t market to anyone other than that … A lot of people don’t belong [in our clothes], and they can’t belong. Are we exclusionary? Absolutely.”

Following Jeffries’ departure as CEO in 2014, Abercrombie & Fitch has celebrated inclusivity, from model diversity and inclusive sizing to gender-friendly clothing.

Brandy Melville has yet to implement such changes. The former Senior Vice President of Brandy Melville, who remained anonymous in the documentary due to ongoing litigation, said that the brand faced backlash following the publication of the Insider article. But, a week later, the backlash settled and the business continued to thrive. This same phenomenon appears to be the case following the release of the documentary, as customers were lining up outside the Brandy Melville store in Toronto a week later.

Addressing other problematic Brandy Melville practices speaks to the larger issues within the fast fashion industry. In the documentary, Kate Taylor, the journalist who wrote the Insider article, said there’s a perception in the United States that the “Made in Italy” tag is a sign of high quality and luxury. However, Ayesha Barenblat, CEO of Remake, an advocacy group for garment workers, challenges this perception, saying that “there are good and bad factories everywhere” and Italy is no exception to sweatshop conditions, resulting in wage theft and unsafe working conditions.

The documentary’s depiction of the post-consumer clothing phase was particularly jarring. Aerial footage shows insurmountable amounts of clothing covering the coast of Ghana, West Africa. Some women have roles as head porters, transporting immense loads of clothing waste that pollute the environment on their heads, resulting in physical health issues like chest and spine pain.

For those who remotely follow fast fashion news, the documentary doesn’t come as much of a surprise. Fast fashion industries consistently exploit their workers with poor wages and subpar work environments, promoting consumer overconsumption and shifting the burden of waste disposal onto less-developed countries. However, the prevalence and alarming normalization of these issues highlight a more concerning issue of why little is done to reverse these effects.

The documentary doesn’t leave viewers hopeless with the state of the fast fashion industry and even highlights possible solutions, but the catch is that they already exist. Sustainable lifestyles, for instance, are much more prevalent with the recent popularity of thrift shops, online second-hand retailers and even simpler habits like buying less clothing. In Ghana, sustainability isn’t just a concept — it is both a lifestyle and language, with people swapping, mending and upcycling clothing to give them longer wearability.

After the Insider exposé, some customers and employees made changes to stop buying from or working at Brandy Melville, but it wasn’t enough to sway the broader consumer community to make effective changes. Perhaps the documentary revealing everything to consumers will convince viewers that they have a stronger pull over these businesses than they realize: not buying into them.