“Demand to hold SBU accountable. Title IX discrimination has become the norm on campus. Students are often left in the dark and silenced.”

This is one of many student messages that can be found on posters throughout Stony Brook University’s expansive campus. They call on students to share their experiences in a survey about the University’s Title IX office.

The seven students behind the survey met this semester in a class called “Democracy and Justice for All.” They were assigned to address an issue on campus — they decided on Title IX.

“We hope that our initiative will change how reports and the website are handled, along with policies,” freshman Zubair Kabir, one of the students on the project, said in an email to The Statesman. “Students should feel as though they are safe in classrooms, dorms, and on campus as a whole.”

Kabir runs the Instagram and TikTok accounts @hold.sbu.accountable as part of the campaign. Stony Brook caught notice of the posts and sent a direct message to the student-run account stating, “We were able to see that site visitors were able to access an old, unmaintained version of our Title IX page.”

The group is set to meet with administrators in early May to address their concerns, including the outdated website and lack of clarity surrounding the reporting process.

“I don’t believe Title IX at Stony is a complete waste, but there’s room for improvement,” Kabir said in the email. “And when the safety of students is in question, it’s important to not brush it under the rug.”

One student who filed a Title IX report in the fall 2020 semester had no complaints regarding her experience. But, as the former president of a sorority, she questions whether or not students view the Title IX office as an effective resource for their concerns. She knows members of her own sorority were hesitant to file reports after alleged incidents with fraternities, concerned they would not receive the help they were seeking.

“It seems like they are reporting these instances and nothing happens,” she said. “Granted, I don’t know. We’re not behind the doors.”

But what students think is happening behind those doors is ultimately what matters. If there is a negative view of the Title IX office, students may be less likely to file official reports.

In 2014, the University’s handling of sexual violence incidents was investigated by the Department of Education’s Office for Civil Rights, along with 75 other institutions. In 2018, The Statesman found that few Title IX incidents resulted in any action against the accused.

Now, Stony Brook has five open Title IX cases. Of these, two incidents were filed in 2017 and three in 2022. The five reports are two sexual harassment cases, denial of benefits, retaliation and “other.”

Christine Szaraz, survivor advocate and assistant director of the Center for Prevention and Outreach, said she has never seen an administration as communicative about Title IX issues as Maurie McInnis’ staff. From previous administrations, there were “crickets.”

After 15 years at Stony Brook, Szaraz says “The idea that we all have a role to play absolutely evolved here.”

The numbers

Title IX refers to the Education Amendments of 1972, which prohibits discrimination on the basis of sex in any education programs or activities receiving federal funding. As part of this, universities and colleges must have procedures in place for sexual harassment claims.

The Clery Act requires institutions of higher education to record their crime statistics, including sexual misconduct. Every year, Stony Brook’s Title IX office releases a sexual misconduct progress report that tracks the total number of reports filed in the past three years. It also breaks down that number by the type of allegation made.

This year’s report listed 177 incidents, a decline from the previous three years. Sexual harassment was up 2.5% from 2021, relationship violence increased 2.6% and reports unrelated to sexual misconduct increased 4.1%. Sexual violence, stalking and gender discrimination all declined.

“You’ve got numbers that I would see more commonly in a school of 40,000 to 50,000,” said Brett Sokolow, president of the national Association of Title IX Administrators, based on anecdotal information through his work. Stony Brook’s enrollment for the fall 2022 semester was 25,710.

But the data may also include reports from Stony Brook University Hospital. The sexual misconduct report form accepts submissions from Stony Brook Medicine and third-party individuals such as guests, visitors or volunteers, potentially inflating the numbers.

What this means

Since June 2022, The Statesman has been analyzing Stony Brook’s Title IX data and seeking out expert opinions on the numbers. But Title IX data is hard to decipher — its nuances prevent experts from drawing conclusions based on numbers alone.

“The variability year to year of reporting is something that’s been mystifying to all of us in the field for a long time,” Sokolow said.

A high volume of reports can mean one of two things on a college campus: greater threat levels or increased accountability.

“Data is tricky — very, very tricky — when it comes to Title IX and what it represents,” said Amelia Barbadoro, the Title IX coordinator at State University of New York (SUNY) Albany. “Truthfully, I can’t tell you if there’s more or less incidents. I’m not there at every frat party.”

Clery numbers also account for all reports filed, regardless of when the reported incident occurred, if it was substantiated or if the case was dropped.

A noteworthy reporting trend occurred when the pandemic struck. SUNY Universities Albany, Buffalo and Binghamton saw significant decreases in the number of reported on-campus rapes when less students were dorming in 2020.

But Stony Brook was different. Despite there being 56% less students living on campus in 2020, the University not only maintained the number of reports, but added one more. There was also no change in the number of Title IX reports filed.

This did not follow the expected U-shaped graph of schools like Binghamton and Buffalo. Through a lens of Title IX reports, it was as if COVID-19 never happened on Stony Brook’s campus.

“It definitely bucked the trend of most of what we were seeing from schools across the country at the time,” Sokolow said.

A data collection and comparison tool created by End Rape on Campus notes that numbers from 2020 were “irregular.” Stony Brook did not see any decrease.

One potential explanation for this is the isolation of the pandemic. Students may have reflected on their experiences — away from their perpetrators — and filed reports online for past incidents.

Or, like the former sorority president, victims were confined near their offenders.

She filed her report after receiving aggressive, inappropriate messages from a classmate. Although she said the Title IX office was quick and calm in their response, she decided not to pursue a formal investigation because the perpetrator lived on the floor beneath her.

“He was just a very scary boy,” she said. “I did not want him to know that I had reported him.”

Students could also report incidents to Stony Brook’s survivor advocate. This is the only non-clinical and non-clergy confidential resource on campus, which offers support and information for victims without mandated reporting. Victims can ask questions and explore their options without having to formally report an incident if they are not ready to do so.

There is also no statute of limitations on reporting. But if a report is filed against someone who has graduated, the Title IX office cannot require them to take part in their investigation.

“We can’t compel them to participate in our practice and our process because there’s nothing to incentivize them,” Marjolie Leonard, Stony Brook’s Title IX coordinator, said. “It can be a struggle for that complainant because they feel like nothing is happening or can be done.”

If students are unsure what constitutes a Title IX case, or what resources are available to them, they are less likely to file reports. New York universities are required by state education laws to survey their students and staff about the prevention of sexual violence at least once every other year.

Stony Brook’s most recent survey results from 2021 found that 94% of students were able to identify on-campus resources for sexual assault, and 74% knew how to report sexual violence to the University.

But the survey only had a 9% response rate. Out of 25,596 surveys sent, only 2,335 students responded.

Title IX incidents are grossly underreported across the country. The Rape, Abuse & Incest National Network (RAINN) found that only 20% of college-age female students report sexual assault to the police, and 32% of non-student females file reports.

The data is complicated — multiple factors are taken into consideration when collecting, reporting and analyzing these numbers. But with these nuances in mind, action can still be taken to improve Title IX issues on college campuses.

Culture of accountability

In 2022, the Office of Equity and Inclusion created a five-part Title IX task force to make recommendations for the response and prevention of sexual misconduct at Stony Brook. All of the groups stressed the need for in-person training and increasing the amount that is currently offered.

“We are aware that with our current times, for a lot of people the convenience factor is online,” Leonard said. “We have 26,000+ students, 15,000+ employees, there’s no way we could get in front of everybody.”

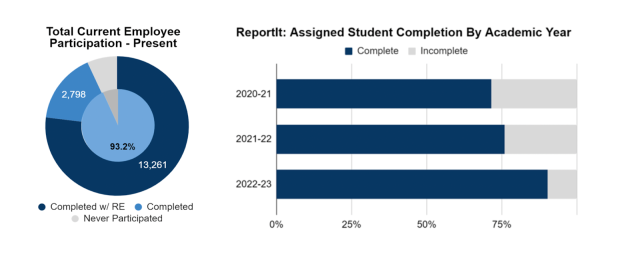

Stony Brook requires an annual ReportIt. training module for University employees, student leaders and athletes. New degree students — whether incoming freshmen or transfers — are only required to complete the training once.

The online presentation covers Title IX reporting through video segments and content checks. Although the videos cannot be skipped through, the content checks can be repeated until all questions are answered correctly. The only consistent engagement is clicking to the next part of the presentation when a video is completed.

But student completion did increase over the past three years, rising from less than 75% in 2020 to over 80% in 2022.

Leonard said that because the ReportIt. training is built in-house by the Title IX office, changes take more time to implement.

“It’s not something that can just be edited and changed within a few weeks,” Leonard said. She affirmed that Stony Brook’s training is up to date with the most recent regulations and information.

At SUNY Albany, Barbadoro tries to switch up training about every four years. Some years she does the presentation herself, and other years the school hosts informative performances.

“What’s effective with that approach is that they’re getting the information in different ways,” Barbadoro said. “It’s not redundant.”

Albany saw reported rapes consistently decrease between 2019 and 2021, unlike Stony Brook.

“The number one reason why our numbers would go down is that we have a culture of accountability,” Barbadoro said.

But with 10,000 more students than Albany, Leonard said in-person training at Stony Brook is dependent on demand. If specifically requested, the Title IX office will coordinate with the inquiring group to provide an in-person training session.

“Over the years we’ve increased the amount of training that we’ve done,” Leonard said. “Our goal is to empower people to feel comfortable coming forward and being aware.”

Social media

Online platforms are a rapidly-growing outlet for students to share their Title IX experiences, especially with student-run and organized social media accounts like @hold.sbu.accountable.

Back in 2020, three fraternities were suspended after sexual assault allegations surfaced on multiple social media platforms. In September 2022, the Sigma Phi Delta fraternity was placed on interim suspension after an Instagram post accused members of sexual assault.

“It’s a messy culture because you keep hearing so many people talking about how Title IX is doing nothing,” the former sorority president said. “Girls and guys always have to run to Instagram or social media because we won’t be heard unless we do.”

The University Police Department has social media accounts that directly reach out to individuals who post about their allegations.

“Students are very proactive in helping their fellow students and making us aware of situations where we can provide assistance,” said Neil Farrell, assistant vice president for compliance, investigations and accreditation at Stony Brook. “I think that really speaks to the University creating a culture that we’re all in this together.”

But President McInnis encourages students to report their experiences through University resources rather than online platforms.

“Social media is rarely the productive place to get this work done, or [for] Stony Brook University to be informed,” McInnis said in a press conference with student media that addressed all issues on campus. “We really hope students, whatever their concerns are, will raise them with official channels as well.”

Students do not agree.

“We are the social media generation,” the former sorority president said. “You shouldn’t have to scream from rooftops to get heard. But if you do, at least it works.”