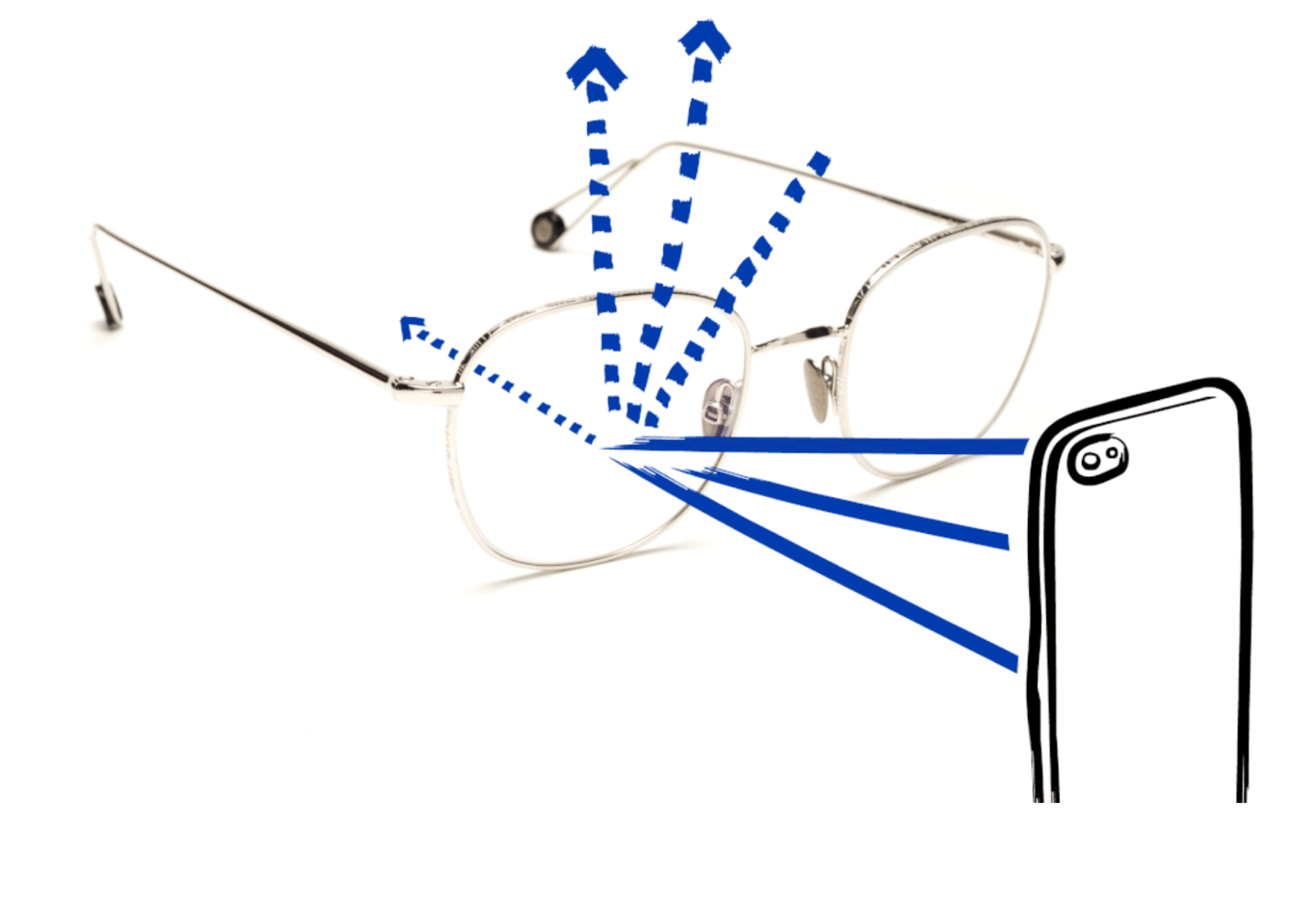

Photo demonstrating how cell phones emit light that peaks in the blue light range. Blue light’s high level of energy has been used in marketing strategies to promote glasses designed to block this particular wavelength of light. AHLEM WEBSITE

Updated Feb. 18 at 2:30 p.m.: This article was updated with comments from Warby Parker.

Increases in screen time since the beginning of the COVID-19 pandemic have surfaced new concerns about blue light and its potential impacts on sleep and eye health.

Cross-sectional and self-reported data from a sample of 3052 U.S. adults showed clinically meaningful increases in screen time in those considered “active” or “inactive” prior to the pandemic.

LEDs, or light emitting diodes, in televisions, tablets, cell phones and computers emit light that peaks in the blue light range. Among all the colors on the visible light spectrum, blue light contains more energy compared to other colors, like red or orange.

Blue light’s high level of energy has been used in marketing strategies to promote glasses designed to block this particular wavelength of light.

The current science behind blue light, however, paints a more complex picture of whether the use of these glasses is truly justified and worth the investment.

Despite attempts by eyeglass manufacturers to market blue light as exclusive to phones, computers, or tablets, this wavelength of light is virtually everywhere.

“The biggest source of blue light is the sun,” Dr. Mark Rosenfield said. “The blue light coming from the sun is thousands or 10,000x stronger than any blue light that is coming off any screen.”

Rosenfield is editor-in-chief of Ophthalmic and Physiological Optics, an international journal in vision science and optometry. Rosenfield has been a professor at State University of New York (SUNY) College of Optometry since 1990, with a career spanning over 30 years.

His 2019 and 2020 studies on blue light blocking glasses demonstrated no evidence to support their use in preventing digital eye strain.

“Both studies showed that the blue blocking filters have absolutely no effect whatsoever on digital eye strain,” Rosenfield said. “The real problem is there’s no mechanism whereby blue light should lead to eyestrain.”

Rosenfield hypothesizes that how individuals use their screens may be one factor to feelings of discomfort reported by heavy screen users. Holding screens at a close viewing distance may cause the eye to work harder.

“The fact they hold them close and the fact that they look at them for hours at a time without taking breaks, I think that’s more of the problem than the screens themselves,” Rosenfield said.

Warby Parker, an online retailer that sells prescription glasses both online and in-store, sells the blue light blocking lenses for $50. According to the Warby Parker website, the glasses “may” aid with eye fatigue.

In an email to The Statesman, Warby Parker Co-Founder and Co-Chief Executive Officer Dave Gilboa wrote that the company started offering the blue light blocking lenses due to an increase of recommendations from doctors and demand from customers. He said that the lenses “filter a significant percentage of the visible light spectrum to reduce exposure,” similar to their standard polycarbonate lenses.

“Blue-light-filtering lenses aren’t necessary for vision correction and the conversation surrounding the effects of blue-light-filtering lenses is still evolving, so while there is a significant amount of research in progress on this topic, it’s unclear the exact impact of blue light on overall eye health,” Gilboa wrote. “We recommend that customers follow-up with their doctor directly for more information about why they recommended this lens type.”

However, Warby Parker isn’t the only manufacturer to market these benefits. Ahlem, a luxury eye brand launched in 2014, sells blue light filter lenses for $180. Its website claims the lens will “reduce eye fatigue and sleep disruption associated with high-energy blue light from digital devices.”

Ahlem did not respond to repeated email inquiries about the science behind its claims in time for this article’s publication.

While the evidence supporting the use of blue light blocking glasses in minimizing digital eye strain is lacking, the use of these glasses to improve sleep may be supported.

“I am pretty convinced that blue blocking filters have no effect whatsoever on digital eye strain,” Rosenfield said. “Where they may have an effect is in sleep because blue light affects the ability to produce a hormone called melatonin.”

Melatonin is a hormone released by the pineal gland in the brain that regulates the body’s sleep cycle.

“Blue light has the potential to affect your circadian system,” Dr. Rohan Nagare, a researcher at the Lighting Research Center at Rensselaer Polytechnic Institute, said. “We have done a lot of studies and so have others, which have shown that short wavelength light especially the blue light can suppress the secretion of the hormone melatonin”

According to a 2019 study published in Lighting Research & Technology, Nagare and his co-authors tested the effectiveness of Apple’s night shift mode on melatonin levels in 12 participants.

“We got subjects to come into our labs in the nighttime and we gave each of them iPads and told them to operate them normally,” Nagare said.

Participants could watch a movie or use their favorite app. Then, night shift mode was enabled for half the study participants.

“Even while using the night shift mode, all the study participants more or less were able to still suppress melatonin,” Nagare said. This study led Nagare and team to conclude that changing screen brightness may also be warranted.

Changing the “spectral” display, or filtering blue light via night shift mode, was not enough to prevent melatonin levels from dropping during screen use.

“It’s important to know that in all of our studies, we always had the brightness setting as maximum,” Nagare said. “So, rather than simply changing the spectrum, you may have to also dim the screens.”

Consumer experiences with the glasses are varied.

Emily Costa, a senior chemistry major at Stony Brook University, has not noticed major changes since wearing blue light blocking glasses, good or bad.

“I don’t feel like [there’s been] a huge difference, but it doesn’t hurt,” Costa said.

But others, like Hana Ghobashy, a Stony Brook University alumni who majored in applied math and statistics, said that the blue-light blocking glasses have reduced the strain on her eyes.

“My eyes feel less exhausted than before I had them,” Ghobashy said.

In a statement released in December of last year, the American Academy of Ophthalmology (AAO) stated that individuals need not “spend money on special eyewear for computer use.” The AAO elaborates that blue light likely does not cause digital eye strain. Rather, how individuals use their screens should be considered.

“I don’t think there’s enough evidence that I have seen to endorse blue light blocking glasses. I think they’re very new. It’s not clear whether or not they should be used and under what circumstances,” said Dr. Pamela Hurst-Della Pietra, a pediatrician and president of Children and Screens, a non-profit research organization that investigates the effects of digital media on child and adolescent development.

For those navigating the new norm of online learning and virtual meetings, Hurst-Della Pietra supports the “20-20-20” rule, also endorsed by the AAO.

“Every 20 minutes, I’ll look at something 20 feet away for 20 seconds ” Hurst-Della Pietra said.

The experts suggest that navigating screen-heavy days may come down to something as simple as minimizing extended periods of screen use.

“Take breaks” Dr. Rosenfield said. “Just making sure the screen is set up appropriately is important, too.”