The Paul W. Zuccaire Gallery’s current faculty exhibition “RECKONING” features works that draw upon collective experiences of our current times.

The topical exhibition, presented entirely online, includes art in a broad range of media. “Rhumb-Line” — an interactive sound installation — sheds light on “climate change, urbanization and habitat destruction” through spatial listening.

Dr. Margaret Schedel, Chair of Stony Brook University’s Department of Art and Associate Professor of Composition and Computer Music, created “Rhumb-Line” with percussionists Brian Smith and Robert Cosgrove, and music technologist Nick Hwang.

In the first of two Salon Talks hosted by the Zuccaire Gallery this fall and now available online, Schedel explained, “This is an instrument you play before you see it.”

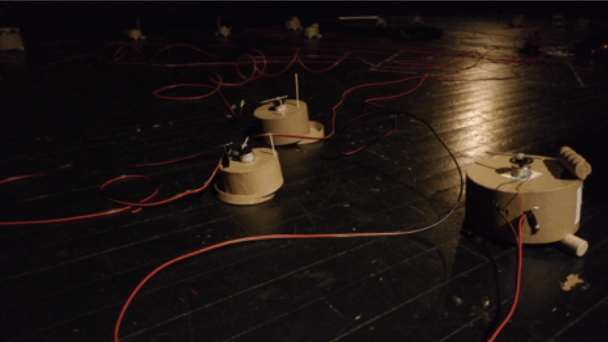

“Rhumb-Line” comprises 19 motorized percussive “frogs,” modeled after the güiro, a musical instrument of Latin American origin. Cosgrove described the güiro as “a resonator that you scratch,” producing “a tremolo sound that is very similar to the way that some frogs vocalize.”

The installation’s frogs are activated when participants input rhythms onto buttons on the website. Participants are then encouraged to listen, first, to the sounds produced without yet viewing the frogs’ formation.

Smith, who constructed the frogs featured in the installation, spent several months researching acoustics and trying out different materials in order to design a güiro specifically for “Rhumb-Line.” Each of the installation’s frogs comprises a resonating chamber (a round cardboard box); wine corks — or feet — to lift the resonating chamber off the floor, and a motor. For the website version of the piece, the collaborators added binaural — or ambisonic — microphones, conducive to surround-sound listening, connected to a head on a motor within silicon ears. Users can rotate the head using the web interface.

Cosgrove explained, “Because the shape of the ears are so realistic and the head is very similar to our shape, it mimics our perception of the sound. What the user is experiencing is literally the sound from what’s inside.”

Smith noted that the individual frogs each have “distinct voices.” Two primary factors contribute to the variation between them: the sizes of the boxes and the striking materials. The striking materials, such as wooden toothpicks, are attached to the motors and generate sound when they hit the upright sounding materials.

As the materials can naturally bend over time, the frogs’ voices, too, can change. Timbre factors into the listener’s experience “in an indeterminate way,” Smith said.

Tuning into different timbres, one “can begin to pinpoint the specific locations of where these frogs are around a virtual pond,” he added. “That’s really the artistic idea behind the piece: can you hear the spatial elements of their calls to the extent that you can guess what their formation is?”

“Rhumb-Line” was first presented live at The Staller Center in February 2020 for “EarFest,” an annual concert presented by the Department of Music’s Electronic and Computer Music Studios. In person, participants remained separated from the frogs (before viewing their spatial formation) by a curtain made of speaker cloth, which was “acoustically transparent but visually opaque,” Schedel said. For the online version, participants are similarly encouraged to listen first, before drawing back the “acousmatic veil” — in this case, virtually.

“I was really interested in these concepts of how sound is so important in nature, and how frogs are a common touchpoint, actually, when people talk about acoustic ecology,” Cosgrove said. “A lot of musicians and sound artists have recorded them, tried to emulate them.”

Cosgrove used Max/MSP, a visual programming language, to program the installation.

“I had a sonic ideal that I wanted to reach for, and I knew how I wanted it to unfold in acoustic space,” he explained. “To compare the two experiences from February to now, I very much felt like I was actually composing something in February. … This time around, I was still composing, but I was composing an algorithm.”

Consgrove called it a “honing process.”

“When you’re working with algorithms, you often don’t get it on the first try,” he added. “I find it very similar to learning a piece of music. The difference is that there’s no score.”

For the current online version, Nick Hwang — assistant professor at the University of Wisconsin-Whitewater — implemented Collab-Hub, a tool he developed that “allows many disparate web objects or computers to be able to communicate quickly and in different topologies,” he said. Collab-Hub enables multiple participants to send control data in interactive installations and music performances by ensembles, including laptop orchestras.

“What I consider interactivity is creating the possibility for something to happen,” Hwang said. The combinations of sounds created in “Rhumb-Line” depend upon chance, due to the interactive — and thus indeterminate — nature of the installation.

Discussing participants’ agency in activating the installation, Cosgrove said, “Every time you add another layer of mediation in between you and the process, there are whole new opportunities — new sonic worlds — that can be accessed. … It’s constantly opening my mind to different perspectives.”

Schedel noted that while participants interact with the installation, they are playing a musical instrument with “an integrated intelligence. … It’s both human and machine together.”

“What we have been really interested in, especially recently, is that the system is an instrument in its own way, too,” Cosgrove said. “A piano has 88 keys; this instrument has [19] frogs. What’s the parallel between a piano, as an ecosystem, and the frogs in their natural environment? How does each single note function within the larger context? There are a lot more connections than you would think.”

Reflecting on the current online version of the installation, Smith said, “The broader picture of species decline I think is really important, and that’s something we leaned in on a lot for ‘RECKONING.’”

Schedel described the installation’s commentary on environmental injustice.

“I’m really inspired by the writings of Bernie Krause, who has done a lot of work on acoustic ecology,” she said. “Frogs and amphibians are really the harbinger of environmental destruction. Their amphibious state makes them vulnerable to both the water and the land, and so for me this was clearly related to ‘reckoning.’”

Schedel explained another example of how recent events have uniquely yielded evidence of ecosystem depletion.

“During the pandemic, a lot of audio researchers have noticed that songbirds are singing more quietly — because they don’t have to compete with traffic — and also expanding their spectral range to where the traffic used to be. It’s been really interesting following people who are audio researchers during this unprecedented, quiet time.”

Zuccaire Gallery Director and Curator Karen Levitov said “Rhumb-Line” importantly addresses “one of the many issues that is of concern at the moment … climate change.”

“I’m specifically drawn to art with a social message — art of social justice,” Levitov said. “I think that as a gallery that’s part of an educational institution, it’s important to have exhibitions and programs that really speak to the students and are relevant to our times.”

Forthcoming exhibitions will include “Dos Mundos: (Re)constructing Narratives” and a group environmental show. In 2016, Schedel and Melissa F. Clarke, curated “RESONANT STRUCTURES,” an exhibition dedicated to sound art and “auditory thinking” — the exhibition catalog is available online.

“I think it’s really great that we were able to do this on Stony Brook’s campus,” Cosgrove said. “There are lots of people working on very interesting things all around campus and sometimes we’re not all connected. … I’m really glad that this has catalyzed some really interesting discussions.”

“RECKONING,” including the interactive installation “Rhumb-Line,” will continue online into 2021.