The fourth annual “Art in Focus” lecture series, co-presented by the Pollock-Krasner House and Study Center and Stony Brook University Libraries, began on Sept. 29 with a presentation delivered by art historian Helen A. Harrison.

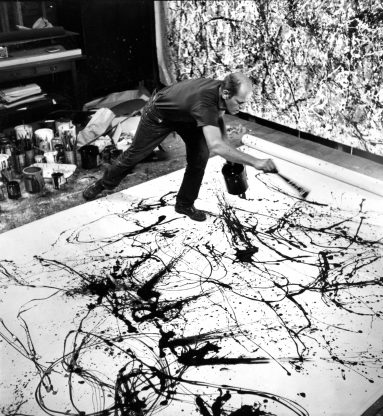

The discussion explored the role of jazz as a possible influence in the work of abstract expressionist artist Jackson Pollock, with a particular focus on paintings from 1948-1950 displaying his action-painting technique.

Harrison, director of the Pollock-Krasner House and Study Center located in East Hampton, devised the “Art in Focus” series in 2017. The Sept. 29 presentation – entitled “Jackson Pollock and Jazz: Inspiration or Imitation?” – was an updated version of a lecture she gave for the Stony Brook University Humanities Institute’s 2008 symposium “Brilliant Corners: Jazz and its Cultures.”

“I’ve always been interested in jazz as a form,” Harrison said in an interview. “When I got to be the director of the Pollock-Krasner House, we had this very large collection of jazz records. I thought, ‘This is an interesting topic. I should look up and see what’s been written about it.’ And the answer was almost nothing. I was very surprised.”

No more than two articles, both published in the 1970s, addressed the subject.

The phonograph record collection’s catalogue, available for perusal online, lists 260 records in two formats: 78 rpm (revolutions per minute) and 33 1/3 rpm discs. The collection’s inventory details a long, impressive list of musicians featured on recordings dating back as early as the 1920s. Included are recordings by influential artists like Bessie Smith, Maxine Sullivan, Edward “Kid” Ory, Louis Armstrong, Billie Holiday, Cab Calloway, Benny Goodman and Duke Ellington. The original phonograph on which Pollock played his records remains on view in the Pollock-Krasner house.

While the collection primarily comprises jazz recordings, a handful of discs include music from acclaimed composers such as Béla Bartók, Paul Hindemith, Maurice Ravel, Arnold Schoenberg and Edgard Varèse. Harrison also pointed out a one-off recording: a reading of literature written by James Joyce.

While at least 127 of the records belonged to Pollock, a portion of the recordings belonged to Lee Krasner, too.

“[Krasner] had a much longer career than Pollock,” Harrison said. “Her early work was figurative. She became quite an accomplished Cubist, but unfortunately it wasn’t very innovative because the Cubist breakthrough had already occurred… But when she and Pollock moved to the country, they both had breakthroughs and really began to do much more imaginative, original imagery.”

Krasner’s work is currently featured in a retrospective at the Guggenheim in Bilbao, Spain.

An abstract painter who attended Harrison’s lecture, Cheryl Rubin, said that Krasner greatly influenced her.

“It’s amazing to be in the house where Pollock and Krasner lived and to see artifacts from their life, whether it was Krasner’s [sea] shell collection, or Pollock’s record collection,” Rubin said. “When you’re an artist, your whole world – everything you see and do in your home, and things you might collect – can be influential in your work.”

Instruction and Reference Librarian at Stony Brook, Chris Filstrup, who also attended, said, “I’ve been out to the Pollock House several times and it’s really unusual to be able to visit a studio. If you think about it, there are not many artists’ studios that survive.”

Pollock and Krasner moved to the house, which is now a National Historic Landmark, in 1945. Harrison notes many of their contemporaries – including Willem and Elaine de Kooning, James Brooks, and Charlotte Park – also resided in the area.

“Then you’ve also got the subsequent generation, up to Cindy Sherman, Ross Bleckner, and Laurie Anderson – people who are now living and working in the neighborhood – and many, many artists who have made Springs into what you would call the East Hampton Art Colony, which originated down in the village of East Hampton in the 1880s. It’s the oldest continuous art colony in the United States,” Harrison said.

The institution presents new exhibitions yearly. Currently on view is Athos Zacharias: The Late Work, curated by Harrison.

“We usually try to do something that would be relevant to [Pollock and Krasner’s] milieu…connected to the New York School, Abstract Expressionism, or the East Hampton Art Colony,” Harrison explained.

One exhibition in 2016 featured the work of female printmakers who worked at Atelier 17, where Pollock made his prints.

Further examining the relationship between Pollock’s craft and music, Harrison’s lecture touched upon Morton Feldman’s score for Hans Namuth’s short film “Jackson Pollock,” released in 1951. Harrison said Feldman composed “as he would for choreography,” filling his score for cello with “intentional fragments that come together as a coherent whole, similar to the way Pollock’s work is made.”

Harrison noted the absence of a record player or radio in Pollock’s studio, confirming that he did not listen to music while painting. A lively question-and-answer session following Harrison’s talk revisited this point.

“I thought the questions were great and I liked the distinction that [Pollock] listened to lots of music loudly, according to [Krasner], in the house, but never in the studio,” Filstrup said. “I thought the conversation about whether jazz was a stimulant or a reprieve, or both at different times, was really enlightening.”

Musician Dave Rubin, who is married to Cheryl, drew a comparison between the musical textures created by soloists and ensemble in early styles of jazz and the visual textures in Pollock’s work.

“Visual representation of music is difficult,” he said. “Music is going on in real time and painting is stable—it’s frozen in time.”

“Art in Focus” lectures previously took place in Southampton. Librarian and Liaison to Stony Brook University’s Department of Art, Claire Payne, co-hosted the lecture. She noted the virtual platform made it possible for viewers to attend who may have otherwise not been able to do so. The lecture drew viewers from New York, Texas and California. Among those in attendance was Ellen Landau, author of the catalogue raisonné of Lee Krasner and the monograph on Pollock.

Harrison’s talk is now available on YouTube. The Pollock-Krasner museum remains open through Oct. 31. The “Art in Focus” series continues this month on Zoom with another lecture on Oct. 27 at 6 p.m.