Stony Brook University’s School of Social Welfare is maintaining field education requirements for its graduating students this semester, according to the school’s dean.

Graduate social welfare students are required to complete at least 33 weeks and 462 hours of field education per year. As classes went virtual due to the ongoing coronavirus (COVID-19) pandemic, students might have expected for requirements to be loosened, however, that wasn’t the case.

“You are making a profound difference in the lives of clients by offering remote services now,” an April 14 letter posted on the school’s Instagram read. “Conversely, there has never been a moment when students can fast track their learning in cutting edge areas — Telehealth, using technology for remote intervention, and emergency preparedness and trauma treatment centers.”

The New York State Department of Education Office of the Professions outlined in its regulations for social work that programs leading to a license in social work must include at least 900 field practicum hours. However, the office announced on March 25 that they will still review applications from programs that have reduced their field education requirements by only 15% or less.

Stony Brook’s School of Social Welfare decided to maintain its requirements out of concern for the clients and communities they serve, the quality of students’ education and at least partially due to the delay in decisions by both the university and New York state, Jacqueline Mondros, dean and assistant vice president for social determinants of health said in an interview with The Statesman.

At Stony Brook, graduate students who register for the minimum four credits of field education in a semester must complete 252 hours during their spring semester. Those who register for six credits must complete 368, according to the Graduate Field Education Manual. Field placements for students can include schools, non-for profit organizations, hospitals, nursing homes and government officials’ offices.

“Most agencies stayed open, but began to work remotely so most of our students stayed in place,” Mondros said. “Then we developed new remote placements with the University, Stony Brook Hospital and many agencies serving older adults.”

If field education requirements aren’t completed, students won’t be able to graduate or take the licensing exam to officially become a licensed master social worker.

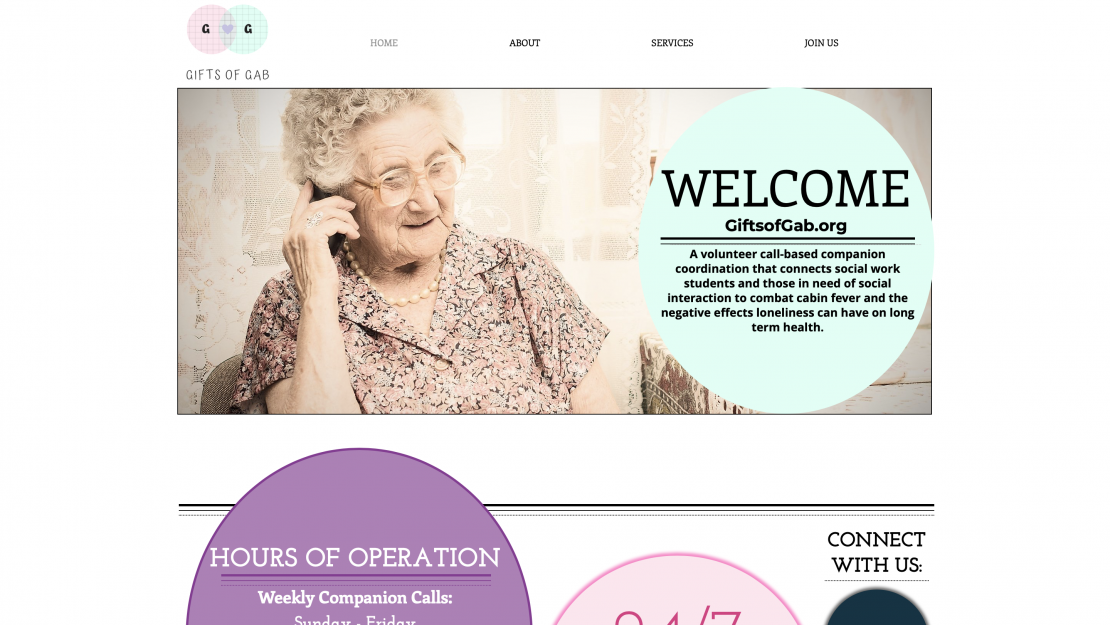

Social working students, however, can still complete their field requirements remotely. One student, partially motivated by the need to fulfill her field hours, created GiftsofGab.org, a website that reaches out to isolated seniors online during the pandemic.

“One of the goals was to aid in alleviating some of those negative side effects of social isolation,” Katherine Maroldi, a second-year master’s student at the School of Social Welfare, said.

Other social work students can volunteer for the website to earn their hours remotely.

“It’s just a blessing that we were able to create something so students can complete the hours,” she said.

Although Nerissa Basant, a second-year master’s student at the School of Social Welfare, completed 531 hours and finished her internship at U.S. Sen. Kirsten Gillibrand’s Long Island office this spring semester, she believes the pandemic may make it difficult for most students to complete the requirement

“I was disappointed that the School of Social Welfare was still keeping the field requirement during this pandemic,” Basant said. “Since everything became remote, people were going through a transition that is not normal to our daily life.”

The Graduate Field Education manual also mentions that “periodically a student may have difficulty completing the required minimum hours in a timely manner due to unforeseen circumstances.” Students experiencing personal or financial problems can apply for an exemption.

Less than 30 students have applied for an exemption from the field education requirements, according to Mondros.

All graduating students from the School of Social Welfare will receive a certificate in trauma-informed care and crisis response. These certificates are unique to the Class of 2020.

Graduates also completed a crisis response training module that was developed to help meet community needs during the pandemic.

Mondros said that the 2020 graduating class is unique in the way they have been able to learn and serve their patients during the COVID-19 pandemic.

“I believe there will never be a class like the one of 2020,” she said. “I am absolutely certain they have learned a lot about themselves too, and years from now when they think about their careers, they will harken back to this as a defining moment.”