In 1958, on the corner of 150th St. and Tinton Ave. in the South Bronx, there was a small grocery store called Krabina’s. Right next to it was a candy shop that featured a jukebox and a television. It cost a quarter to watch for five minutes.

Right outside the shop stands a 20-year-old Martin “Marty” Doherty. His hands are in his pockets, his shirt is freshly pressed, his hair is neatly combed and his shoes are newly buffed. Not one hair is out of place.

Standing with his younger brother and his friends, he is confused as to why there are also six younger girls. He’s not used to spending time with girls. One of them, Jeanie, comes to stand next to him. He stands at 5 feet 10 inches, only two inches taller than her. Only two inches taller than he needs to be.

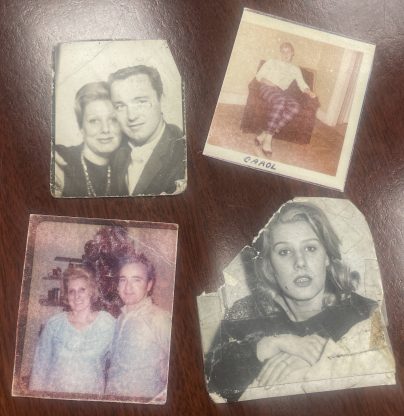

Carol — a 17-year-old girl with them — was satisfied with this height.

A year and a half later and seven months pregnant, Carol and Marty were living in an apartment on 22nd Street in Manhattan. On July 3rd, 1960 she asked him when they were going to get married. On July 4, they were married by a priest in the Bronx who didn’t think they would last three months.

Every year, that same priest receives a letter from Marty, thanking him for officiating the ceremony.

63 years later, Marty’s eyes still shine when he tells this story. Unfortunately, he lost Carol to cancer seven years ago. The pictures of his wife in his wallet are worn and well-loved.

“She’s very photogenic, the most amazing talented person I’ve ever known,” he said with a bright smile on his face. “She liked me ’cause I’m funny. I liked her ’cause why wouldn’t I?”

Marty met Carol after leaving the Marine Corps. Though it was a brief stint, Marty is grateful for everything that came from his service.

“It was a happy, happy time, and I would not be where I am today without everything they gave me,” he said.

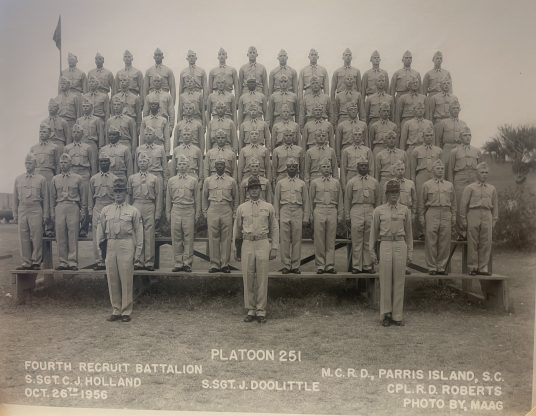

Taking the train from Penn Station down to South Carolina at the age of 18, Marty became a recruit, training for the Marine Corps at Parris Island.

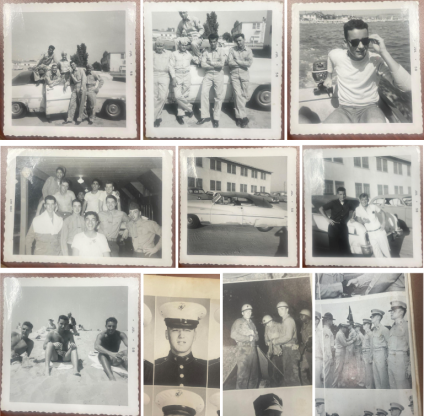

His time in the Marine Corps, where he served from 1956 to 1959, was marked by various adventures.

In the Corps, Marty embraced the military lifestyle, appreciating the cleanliness and organization of the bases. He engaged in diverse activities with his fellow Marines, such as betting on horse races and enjoying music at the Hollywood Bowl.

Marty was stationed in different places across the country, including California. Every day was an adventure for him, despite having absolutely no combat experience. From buying a rusty car that he used to drive his comrades around in, to stealing a flag from Disneyland as a form of protest when the park did not meet his expectations, he made the most of his years in the service.

No matter where he went, Marty always brought his “Bronco” mentality. He vividly recalled an incident at a theater in North Carolina where a fellow Marine, Private Jenkins, was denied entry due to his race.

“He was defending his country, and he couldn’t sit in the theater?” Marty said. “I started screaming, I was cursing. I went crazy. I grew up in the Bronx surrounded by every nationality you can have, it didn’t make sense to me.”

Although Marty’s time in the service was not marked by combat, he excelled in marksmanship, becoming an expert rifleman despite initially hating the glasses that were issued to him as a recruit. These glasses allowed him to actually see the target.

“I never had glasses a day in my life,” he said. “I thought the world was blurry for everyone.”

However, as fate would have it, his glasses became an unexpected ticket out of his military duties, allowing him to finish his service in only three years since he was unable to become a pilot.

If he had not left the military at that time, he would never have met Carol the following year.

“I hated those glasses but they were the best thing that ever happened to me. I could never have met a better person in my life,” Marty said fondly.

Following his service in the Marines, Marty transitioned into civilian life and found employment with the US Parcel Service. This was another chapter in his life, marked by hard work and commitment.

In 1967, after Marty and Carol had been married for seven years, they accompanied some friends on a trip to Long Island. They took the Cross Bronx Expressway to Exit 61, the very last exit into Lake Ronkonkoma, and pulled into the driveway of a model home with a sign that read “G.I.’s no money down.”

Within a week they were settled into their new home where they would raise their six children. The house became adorned by Carol’s artwork. She spent hours creating intricate art pieces, including sewing pictures and seasonal flowers for her children and grandchildren. She stitched their life journeys from childhood to adulthood into a beautiful tapestry.

However, Marty’s time in the service was not yet over. At a recruiting event at Smith Haven Mall, he decided to enlist in the National Guard. He served not just once, but twice, out of a personal commitment to helping young recruits. He wanted to tell them not to take anything too seriously and enjoy their time in the service the same way he had.

“There was no one like that for me, so I just wanted to be a cheery face for these boys,” he said. “That was really it.”

He spent 13-14 years in the National Guard before retiring. “A lot of guys say they retire from the military, but I’m one of the few who actually did,” Marty said jokingly.

In 2006, after his retirement, Carol was diagnosed with a life-threatening condition in her spine. Remarkably, she kept her struggles to herself — a testament to her strength and resilience. She faced the pain and discomfort with unwavering grace, symbolized by her limited complaints and her stoic resolve.

Later, she was diagnosed with cancer. Despite enduring years of chemotherapy and medical treatments, her condition only worsened. The cancer metastasized, reaching her lungs and later leading to neuropathy in her feet.

As her condition became more severe, Marty continued to support her unwaveringly. He was not just a loving husband, but also her steadfast caregiver. He remembered every detail of her treatment, from the change in medications to her various symptoms.

When she began losing weight, Marty had to make choices about her care. He explored different treatments, even reaching out to North Carolina for specialized medication. However, her condition only continued to worsen.

Eventually, she was transferred to hospice care, a place where he never expected to find himself. Marty’s hope that she would recover slowly diminished, but his dedication to her never faltered. He chose to celebrate her life rather than dwell on the pain of her passing.

“The hospice in Port Jeff[erson] wasn’t a sad place for us. She was only there for a day before passing, but that was a day of celebration, not of grief,” he said.

The hospice became the setting for their final moments together, so Marty and his family ensured that the time they had left was filled with love, support and cherished memories. He was by her bedside when she took her last breath. It was a moment of profound loss, but it was also a moment of immense love and connection.

At the age of 84, he does not have a single health issue and chooses to devote most of his time to the Long Island State Veterans Home.

“I want to use my health to help them since they’re not as lucky as me,” he said. “After my wife died there was nowhere for me to go, and nothing for me to do, so here I am. I can make a difference, I can talk to the residents — I know them. I am them. That’s why I’m here.”

Open the book “100 Years of Making Marines,” flip to page 84, and you will see a picture of a group of recruits at bayonet training. All of them are grunting, with intense looks of concentration. Oddly enough, one of them has a carefree smile on his face as he stands crouched, thrusting his spear into an imaginary enemy.

“I made it into the book, and I look like a clown,” Marty said. “I’m training to kill a man, and I’m smiling. If any picture could describe me, that would be the one. It was never that serious, I believe nothing ever is, and if I can remind even one person that, then I’m using my time well.”

Marty continues to smile every day. He still lives in the same house that he and Carol bought together in Lake Ronkonkoma. Her creative presence remains vivid. The house is adorned with her handcrafted art, a lasting testament to her artistry and the love she had poured into every piece she created.

“The house is a memorial to her, I will live there for the rest of my life,” Marty said. “I don’t miss her. How can I when she is there?”

Every morning when he walks down the stairs into the kitchen and looks out through the window to his pool, he smiles as he sees two signs hanging on the fence he built around his yard.

Old street signs — one reading 150th St. and another reading Tinton Ave. — hang there, stolen from the South Bronx one night in the 1960’s.

“I had a good life. Maybe the best,” Marty said. “I think everyone lives a good life. We just don’t realize it until it’s almost over.”