Christine Kelley is a writer from the Virginias and The Statesman’s opinions editor. She is also a featured blogger at Eruditorum Press.

As I step into Battery Park for the first time, I’m surprised by all the wrong things. The 4 train drops me off just south of Bowling Green. I don’t immediately notice the Statue of Liberty; when I do, it’s just an over-signified speck on the horizon, another tawdry landmark in Manhattan.

As I walk past a hedge, I see a huge sandstone rotunda in the distance. I swallow hard, and unsuccessfully try not to cry. With my heart in my throat, I trot briskly towards Castle Clinton, Battery Park’s fortress-turned-immigration-station-turned-aquarium-turned-tourist trap. When I arrive at the gate, I break down crying.

It is Oct. 23, 2022. I am crying outside Castle Clinton because in a way, this is where I was born. I have never been to Battery Park in my life. But a part was here long ago: 139 years and two weeks earlier.

On Oct. 9, 1883, my second great-grandmother Anastazie Princová arrived at Castle Clinton, then called Castle Garden, Lower Manhattan’s immigration station before Ellis Island. Anastazie was 16, Czech and completely alone — a precarious set of things to be in 1883’s America. An underage Slavic girl crossing the Atlantic alone was as liable to survive as an icicle in the upper echelons of Dante’s Inferno.

Anastazie was one of 8 million immigrants who passed through Castle Garden between 1855 and 1890. America was particularly hostile to immigrants in the late 19th Century, long before ICE terrorized undocumented immigrants and citizens by birth. The Page Act of 1875 and Chinese Exclusion Act of 1882 blocked Chinese people from immigrating to America, while the Immigration Act of 1882 levied restrictive taxes against migrants and imposed an entry ban on disabled people and alleged criminals.

As I circle around Castle Clinton’s sandstone rotunda in 2022, I see a different culture: one happy to erase the atrocities of American history. A stone plaque by the port commemorates World War II-era Norwegian soldiers who allied with the United States. A banner by the ferry quotes John F. Kennedy: “Everywhere immigrants have enriched and strengthened the fabric of American life.” Perhaps Kennedy’s country should have considered that when it turned away Jewish refugees from Nazi Germany.

It’s hard to tie sentimental quotes from Kennedy to current events. Even after the racist and xenophobic Trump administration, the United States is furthering anti-immigration policy. The Biden administration is expanding immigration Title 42, which has blocked more than 2 million immigrants, to turn away Venezuelan asylum seekers. Republican politicians like Ron DeSantis are forcibly relocating migrants, while Republicans continue to push anti-immigrant legislation. From beyond the grave, Chester A. Arthur is nodding approvingly at U.S. politics.

Anastazie, or “Stazi” (a perfectly innocent nickname before the U.S.S.R. purloined it) was herself a victim of empire. Weeks after her birth, the Austro-Hungarian Empire formed, continuing centuries of occupation in Anastazie’s native Czech lands. Her people, the Bohemians, were second-class citizens in their own land, where Germans suppressed them long before anybody had ever heard of Adolf Hitler.

The Princ family seemingly lived happily in Blatná, an ancient rural town in South Bohemia. Their patriarch Josef was a respected local farmer who won cash rewards for his sunflowers, cabbage and hemp (seriously). Josef and his wife Marie had 13 children. Eleven of them lived to adulthood. Anastazie was their third child, and she must have been close to her family — five of them later followed her to Cleveland, Ohio. Marie even visited her six children in Cleveland; dozens of people paraded her to Blatná’s train station to see her off.

But a happy Czech community wasn’t enough to keep Anastazie in Bohemia. The Habsburgs and Austria-Hungary brutally repressed Czech revolutionaries in the 1840s, causing a wave of immigration from the country. Another one followed after America passed the Homestead Act, promising land to immigrants, an appealing bargain for Czechs suffering under Teutonic rule.

When she was 16 years old, Anastazie embarked on a 60-mile journey, either on foot or by wagon from Blatná to Prague, and then a train or boat voyage to Hamburg. She then spent two weeks in steerage (lowest class transport) on the SS Hammonia, with no windows, bunks that crowded as many as five people together and a ceiling that rose maybe five feet.

I think about Grandma Stazi’s journey when I take the train to Battery Park. Initially I’d planned to have company for this trip, but that fell through. So I take the pilgrimage to Castle Clinton alone. History repeats itself; genealogy repeats itself like a beloved elderly relative that shares the same anecdotes ad nauseam.

I don’t know why Anastazie left on her own, or why she was the first Princ to leave Bohemia. As the third oldest child of a Czech family, she should have gone with her parents or followed an older sibling. The only hint I can find as to her solo departure is in ships records, which indicate that she traveled under her mother’s maiden name: Šebesta. Perhaps she was honoring her mother and rejecting her father.

When I get to Castle Clinton, I walk around the building, scanning the whole area before entering the old fortress. I want to see where Grandma Stazi walked before entering the facilities. The old fortress was built for war but never saw military action. The National Park Service — which maintains the building — would like to have you think that, as a cannon has been set up inside the rotunda. Tourism is always about preserving a past that never happened.

Castle Clinton is a shell of its 1883 self. It’s lost the roof and additional floors it once had. What’s authentic, however, are the sandstone walls. As I caress the rough sediment, trying to avoid the dusty remains of bird dung, I wonder if my double-great grandma did the same thing all those years ago. The walls have some crannies. Maybe Anastazie sat in them for shelter.

Like Grandma Stazi, I also fled once. Running has become so normal to me that staying is the struggle now. Maybe I got that runnin’ gene from Anastazie.

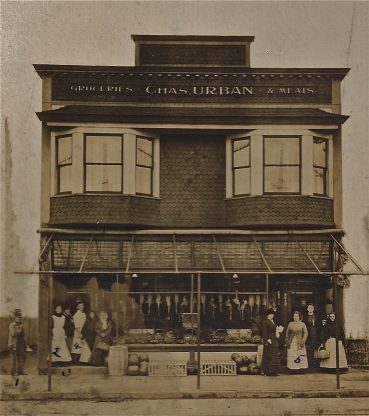

Like me, Anastazie found a home: hers was the Industrial Midwest, where Czechs were settling in eastern Cleveland, Ohio. She married Karel Urban, a Czech carpenter, had five children with him, adopted her husband’s two orphaned nieces and ran a grocery store for nearly 60 years.

After she arrived, five of Anastazie’s 11 living siblings joined her in Cleveland. Her older sister Marie moved in next door to the Urbans. This wasn’t a found family as such, but a lost-and-found family. Her greater found family was the Czech diaspora in Cleveland, who played a part in founding Czechoslovakia.

Grandma Stazi was hardly a major victim of America’s xenophobic immigration system. While 19th century America had no shortage of anti-Slavic sentiment, Anastazie was still a white lady, bound to have an easier time in America than her Jewish and Chinese contemporaries.

But first, she had to be a working-class girl crossing the Atlantic. She supplied her own food in steerage. In Manhattan, she faced medical examination by an America that believed immigrants were disease carriers. And then she would have had to prove that she wasn’t a sex worker.

Castle Clinton doesn’t have many signs of that. As landmarks go, it feels like an afterthought; it is only the cannon and metal grids on its windows making it look like a battleground that it never really was. Grandma Stazi probably sat against these walls, but she wouldn’t have recognized the display there now.

The closest thing to Anastazie’s Castle Garden is a miniature on display. A small layout, flanked by two others, depicts Battery Park in 1886, just three years after Anastazie’s arrival. The port where the SS Hammonia docked is more clearly demarcated. Nowadays it’s paved over, with a restaurant lording over where the port once was.

Before raising her family, Anastazie participated in Sokol Cleveland, a Czech diaspora organization, representing Cleveland’s Czechs at home and abroad in Prague by the time she was 20. When she died at 78 years old in her house in Cleveland, she was a beloved member of her community.

Anastazie not only had an optimal life for a 19th century immigrant; she used her immigrant life to exalt the people around her.

Tragically, the Czech side of Cleveland has declined under heavy gentrification and poverty. The Czechoslovakia they founded fell victim to Hitler by the 40s. And the fascism Czechs opposed in Anastazie’s time is resurfacing in some of the anti-immigration policies that might have blocked Anastazie’s arrival.

I’ve spent my whole life looking at pictures of Anastazie. Over the summer, I’ve been researching her obsessively. But it wasn’t until I arrived at Castle Garden that I finally understood. This is where I was born, where Anastazie began my family’s story of making life out of struggle. In a xenophobic, anti-Slav country, Anastazie Urban found her own community.

I hope I inherited her penchant for settling, not just her inclination to run. If I could interview any historical figure, it’d be Anastazie Urban. Nobody can teach me more about thriving and uplifting myself and others than the little Slav who outlasted empires.

Brian G. Andersson • Nov 1, 2022 at 9:22 am

Tuesday, 1 November 2022

Christine Kelley – As an expert in Castle Garden-era arrivals and as a devoted and noted genealogist, I completely and utterly know how you felt when you came to my hometown and visited Castle Garden. It has an amazing history and predated Ellis Island for arriving immigrants. It functioned as New York State’s “Emigrant Depot” from 1855 to 1890, when the Federal Government finally stepped in and established its Inspection Station at Ellis Island. Castle Garden functioned differently, providing currency exchange, rail tickets, and referrals for safe lodgings. It must also be pointed out that Ellis Island was an inspection station, not a welcome wagon. Further, contrary to popular myth, no names were ever changed by any immigration officials.

Castle Clinton, as it was previously known before and after the Castle Garden years (you ought to read its history) was built for DEFENSE, not “war” as you preferred to characterize the early years of our republic.

I was just sorry that you used your article to enunciate your angry political views. Castle Garden deserves better.

– Brian G. Andersson