Liam Noonan is an assistant archivist at The Statesman and a BA/MAT student in Stony Brook University’s School of Professional Development. This article is co-written with aead archivist Kelcie Eberharth, an editor at Stony Brook’s Undergraduate History Journal and President of Stony Brook’s History Club.

Since its foundation in 1957, Stony Brook University has experienced a variety of student protests, earning it the reputation of “The Berkeley of the East.” One protest in particular, referred to as “Tent City” by its organizers, underscored the poor compensation of graduate students employed through the University.

A 1985 piece written by Christina Voulgarelis covered the beginnings of the Graduate Student Employees Union’s (GSEU) protests against poor compensation for graduate students. The rally featured representatives from the GSO, NYPIRG, SASU and UUP speaking on issues ranging from investment in South Africa to graduate student salaries. Local president of the GSEU chapter Kevin Delaney cited that in spite of the $5,300 graduate students make annually, they teach as much as 50% of all undergraduate courses.

Mitchell Horowitz provided an overview of negotiations between the GSO and the University Senate in a 1987 piece titled, “Senate Backs GSO Living Improvements Plan.” The Graduate Research Initiative (GRI) was crucial to the plan, which aimed to improve the graduate and research programs at Stony Brook. The GSO proposed a resolution to the University Senate requesting that 50% of the money appropriated for the GRI be allocated, “to improve the current quality of graduate-student life.” While the resolution was passed by the Senate, many thought it was unlikely their requests would be met in entirety.

Another 1987 piece covered by The Statesman demonstrated Stony Brook’s reluctance to compromise with the GSO, as requests for pay raises were met with negligible accommodations. University top administrators agreed to “a $1,000 yearly stipend hike” to alleviate some of the financial burdens placed upon graduate students, raising the stipend for graduate students from $6,000 to $7,000. However, many graduate students in liberal arts departments still felt as though further strikes were necessary as their request for an $8,000 yearly stipend had not been met.

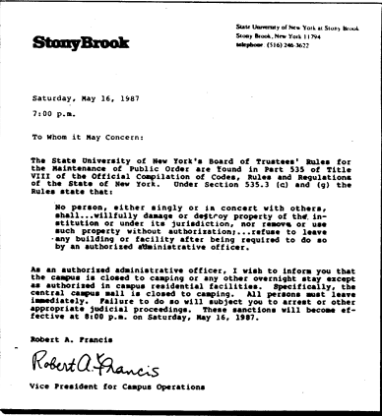

The protests were exacerbated by the hostility of higher University officials towards the protestors, as demonstrated by The Statesman’s 1987 piece, “Francis Evicts Grad Students from ‘Tent City’.” Vice President for Campus Operations Bob Francis issued a memo, “forcing graduate students to dismantle the self-dubbed ‘Tent City’ in one hour or risk arrest.”

Francis’ effort to shut down the protests accomplished little more than prolonging them, as he was met with pushback condemning his reluctance to cooperate with protests and his “infringement” of the students’ rights to assemble. Chris Vestuto, GSO president, believed Francis’ actions severely eroded the foundations of trust built between the University and the protestors over the course of the demonstrations.

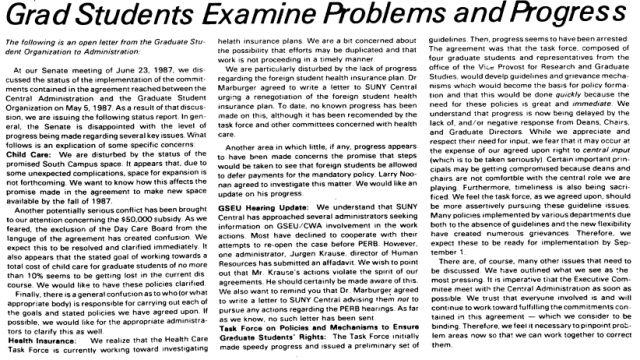

Following Vice President Francis’ eviction of GSO protestors from ‘Tent City,’ a meeting was held by the GSO Senate to evaluate the progress made in advancing the rights of graduate students. In an open letter from the GSO to University administrators, members voiced their concern for the lack of attention given to many of their key points. As far as health insurance for both domestic and international students, it was said that headway had been made. Similarly, guarantees for the rights of graduate students had made little progress as the proposed Task Force halted their efforts soon after their initial formation.

Although the Tent City protests occurred over 30 years ago, the problems they highlighted in the University’s treatment of graduate students persist to this day.

The problem of wages for graduate students remains in the minds of both the University administration and the GSO. This comes as the wages of Stony Brook graduate students remain beneath the local poverty line, and other actions of protest have been taken. Little progress has been made in favor of these students, as many of them are forced to take up side jobs in order to make ends meet. The future of this movement remains uncertain, but Stony Brook graduate students have a long history of advocating for themselves and their needs.