Cuts, scrapes, breaks, aches, pains, sprains, fractures, tears — these are all terms that can be used to describe an injury that occurred on or off the field. The list goes on and on, and only a few are easily treated. However severe, Doctors are usually able to tell what the problem is right away and put their patients on the path toward full recovery. Break your arm? Put a cast on and let it heal. Tear your ACL? Undergo surgery and partake in a grueling rehab process. Suffer a concussion or another form of traumatic brain injury (TBI)? Slap a Band-Aid on it and run right back out there champ.

This outdated approach to player safety and the dangerous long-term health repercussions of brain injuries, was the center of debate on March 28 when the Stony Brook University Program in Public Health and Stony Brook University Neurosciences Institute hosted a public symposium, “Contact Sports and Traumatic Brain Injuries.”

The first portion of the symposium was led by Dr. Chuck Mikell, the co-director of the Stony Brook Movement Disorders Center and an assistant professor of neurosurgery at the Renaissance School of Medicine. Dr. Mikell, a former high school football player, discussed the basic science and medical processes of concussions and TBI as well as some of the long-term consequences of participation in contact sports. Dr. Mikell specifically mentioned amyotrophic lateral sclerosis (ALS), also known as Lou Gehrig’s Disease, and chronic traumatic encephalopathy (CTE) as the two most prevalent issues concerning those who have played contact sports.

Dr. Amy Hammock, an assistant professor of social welfare and a faculty member in the program of public health, found that what Dr. Mikell spoke about hit very close to home. “I feel like I learned a lot about the inflammation that occurs and can keep occurring for years after. There really is very little that can be done after the fact … I have a son who is 5 years old, there is no way he is ever playing football.”

Following Dr. Mikell’s, Dr. Anat Biegon, a professor of radiology at the Renaissance School of Medicine discussed how the human brain responds and acts during episodes of TBI. This included how these episodes incur long-term consequences and how children are put at greater risk for these same conditions due to their age and the makeup of their skeletal system.

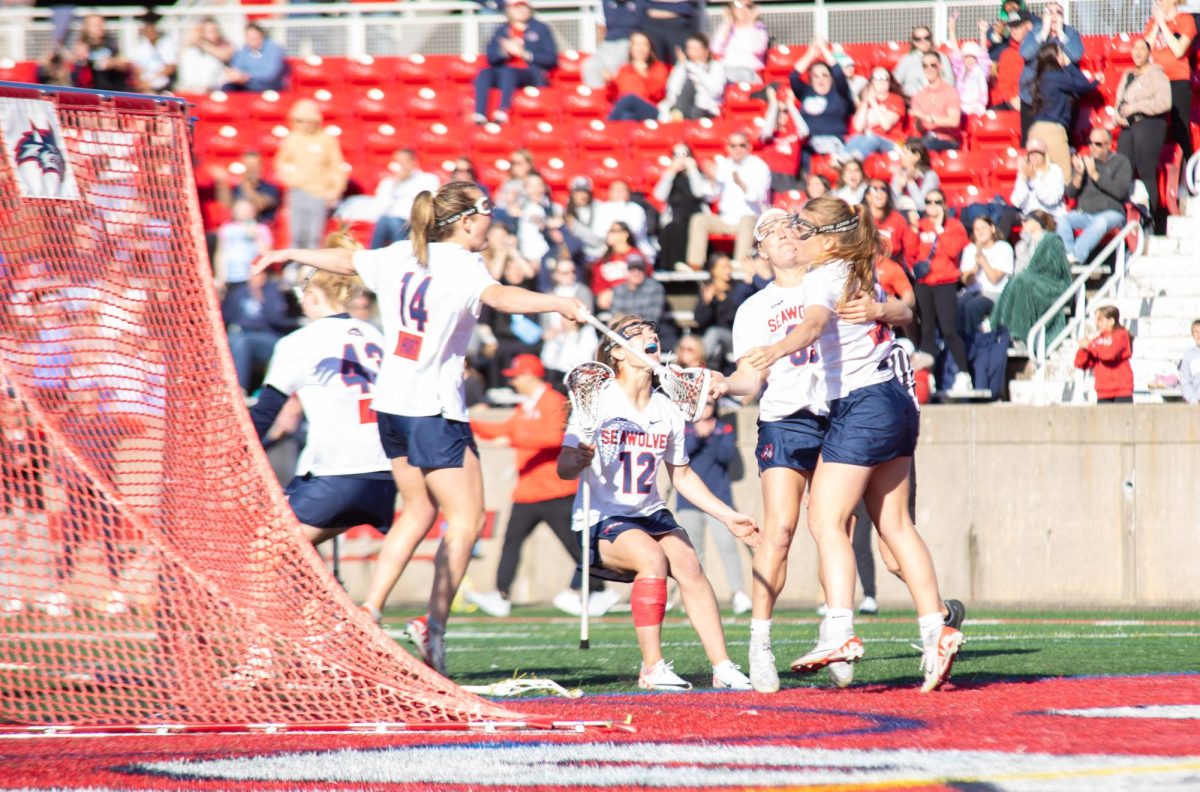

The final guest panelist, Dr. Paul Vaska, a biomedical engineering and radiology professor at the Renaissance School of Medicine, changed the direction away from the problems playing contact sports and towards the solutions. He discussed in detail some of the ways that companies and organizations are trying to minimize TBI and concussions in contact sports as well as everyday life. Two examples included creating better helmets to protect athletes and implementing eye tracking technology to help diagnose concussions and TBI. Vaska’s department also studies Stony Brook student-athletes. The athletes, most commonly from the football and lacrosse teams, sign waivers prior to the start of the season allowing Vaska to image their brain following a concussion. Vaska stated, that 34-51 hours after the injury occurred the athletes brains are imaged, and again three months later.

Dr. Lauren Hale, a professor of family population and preventive medicine, had no issue stating her opinion of collegiate athletics. “I probably have a bias against universities investing money in sports programs. This presentation reaffirmed my belief that it should not be a priority.”

Dr. Andrew Flescher, a professor at Renaissance School of Medicine department of family, population and preventive medicine and a faculty member in the Program in Public Health, who moderated and coordinated the symposium, ended by discussing the safety crisis in contact sports. He talked about the risks and rewards of such activities as well as the social value that participation in contact sports has. He also discussed that a lack of correct information and a wealth of misinformation has prevented players and parents from making reasonable, informed decisions about playing contact sports for years.

Dr. Flescher has become torn by his occupational allegiance to the facts as a scientist and his emotional allegiance to the game as a lifelong New England Patriots fan. “I can tell you stats, who won the Super Bowl going back to Green Bay winning the first two. It is an exhilarating sport, but the thrilling moments are the most dangerous. I have serious cognitive dissonance about football.”