In a crowded theater at 2 p.m. on a Saturday, silence reigns as the image of an upside-down, black and white American flag fades into darkness. This is the effect of “BlacKkKlansman.” Buried in the story of a Ku Klux Klan infiltration in the 1970s is not only a reflection but a summary of modern-day race issues and a blatant call to action.

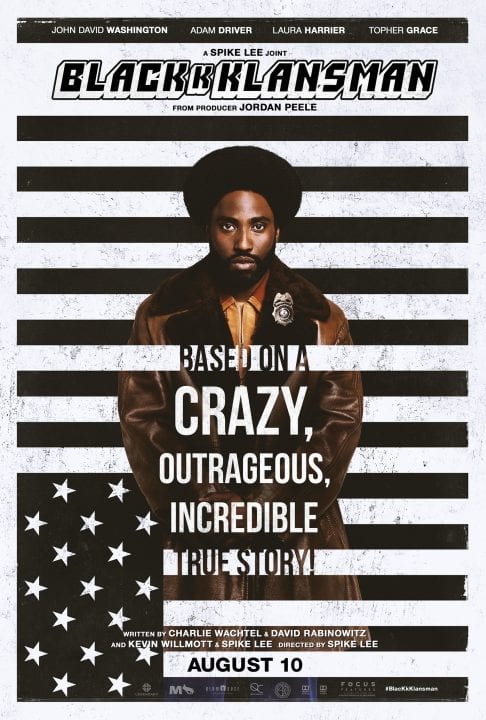

The newest film from director Spike Lee and producer Jordan Peele tells the story of Ron Stallworth, based on his 2014 memoir, “Black Klansman: Race, Hate and the Undercover Investigation of a Lifetime.” Stallworth (John David Washington) was the first African-American police officer in Colorado Springs, who launched an infiltration of the Ku Klux Klan. After arranging a meeting with the local chapter, Stallworth sends his Jewish colleague, Flip Zimmerman (Adam Driver) in his place. Zimmerman and Stallworth assume the same identity, with Stallworth communicating over the phone and Zimmerman in person, as the fake Ron Stallworth becomes a member in good standing of the Ku Klux Klan.

Now insert a series of increasingly uncomfortable scenes, from Zimmerman’s perilous treks into the homes of Klan members, to every phone call Stallworth shares with David Duke (Topher Grace). Every racist remark out of the mouths of Zimmerman or Stallworth is met with a hard cringe, and comedy is utilized to make viewers squirm. The irony is almost funny as Stallworth declares, “Put my mouth to God’s ears, I really hate those black rats.” Almost.

Assistant Professor of History Robert Chase, thinks it’s important that Americans of all racial and ethnic backgrounds understand the role that law enforcement has played in the history of domestic political surveillance.

“I do think that this movie is an important film that reveals how police departments engage in the surveillance of domestic political organizations,” Chase said. “But I think that the focus on the KKK alone does not tell the full historical story.”

Though the film is primarily focused on racism toward African Americans, the Jewish role in history was not missed. In a prelude to the movie, a 1950s Alec Baldwin stumbles through lines for a video of propaganda, in which he blames “Jewish puppets” in government for the problems with society. In another shot, Zimmerman ponders his ethnicity, discussing how he never considered his Jewish heritage, but, “Now I think about it all the time.”

“BlacKkKlansman” also stresses its setting in the 1970s, utilizing the time period to make its references to modern day even more unsettling. Sitting in a wood-paneled office in a tan suit, Duke tells Stallworth, “That’s why we need more people like you and me, for America to achieve its… greatness again.” In another shot, Stallworth scoffs at the idea of Duke running for office, saying that someone like him would never get elected.

“I’m really big into racial equality and social justice,” Sabrina Donzelli, a senior biology major who has seen the trailer and is excited to see the film, said. “To see a person of color try to get dirt on a terrible supremacist, I think that’s awesome.”

The implications about today’s world are clear from the start and Lee holds nothing back. From referencing Donald Trump, to seeing Stallworth’s police officer colleagues pull over a car of African American students only to harass and abuse them, the message is clear: things haven’t changed. Not enough. By the end of the film, the story is no longer about Ron Stallworth or the movements in the 1970s – it’s about 2018. Clips of the 2017 Charlottesville white nationalist riots and a video of the real-life, still-going-strong David Duke endorsing Donald Trump are startlingly similar to the events depicted in the film, and Lee’s placement of these clips in the movement blurs the lines between yesterday and today.

“The film does highlight that white radical organizations like the KKK had a violent after-life beyond the civil rights movement,” Chase explains. “The tragedy at Charlottesville, VA during the ‘Unite the Right’ rally in 2017 demonstrates that such white right-wing extremism remains violent today.”