Content warning: sexual violence

Tyre Nichols, a 29-year-old Black man, was threatened, pepper sprayed, tased and brutally beaten by five Memphis police officers on the evening of Jan. 7.

The sounds of Nichols begging, pleading and crying for his mother were ignored. He lay on the pavement bleeding, just 100 yards away from home.

This came after officers pulled Nichols over for a traffic stop following alleged “reckless driving.”

Officers immediately used excessive force for the entirety of their encounter with Nichols despite him exhibiting no dangerous behavior. Following the vicious abuse and violation of his rights, Nichols passed away at St. Francis Hospital on Jan. 10 — his face so horribly battered he was unrecognizable to loved ones.

There are countless instances of police brutality throughout American history but, in the last 10 years, there has been increased attention toward police violence. The response to the killings of Trayvon Martin, George Floyd, Breonna Taylor and Eric Garner all exemplify this.

Yet, coverage of these victims will often fixate on alleged criminal pasts or decry them as “no angel” without placing blame on police officers.

The biggest question is: Why is the public perception of police brutality focused on the “violent” offender rather than the police officers responsible?

Let us go back to the United States in the 1990s — a country plagued by crack cocaine, violent crimes and major police reform.

During this era, two FBI agents began to investigate and conduct interviews for a study they titled “Killed in the Line of Duty.” One leader of the study had experience as a police lieutenant, and the other was a Catholic priest with a doctorate in psychology. They decided to analyze the motives behind the actions of convicted police murders.

Over three years, the duo interviewed 50 offenders that were responsible for the deaths of 54 police officers. The leaders of the study investigated what characteristics the murdered police officers shared, in addition to the psychological health of the offender.

The study garnered national acclaim and was even featured on the front page of The New York Times. As a world-renowned news outlet, the impact of their words can heavily sway the minds of those who read to inform themselves on race and politics. The 1992 study’s prestige, doubtlessly boosted by The Times, has made it a lasting and influential document in policing.

The study’s conclusion showed that police officers killed in the line of duty by those interviewed were “good-natured” and overall friendly individuals who used little to no force with offenders. The officers’ amiable behaviors made them well-liked in their communities, as well as in their departments.

In addition to this, the study reiterated that the behavior of an offender is what makes an encounter aggressive.

While the study had no ill intent, it unintentionally informed modern understanding of police brutality.

This interpretation soon reached the ears of police departments nationally. Some analysts have suggested that it led to a change in officers’ mindsets, treating all perceived offenders as threats to their safety.

Officers arguably then started to treat all offenders they encountered as potential threats to their safety. The instilling of a “dominate-or-die” notion amongst police is still prevalent today and is heavily exhibited by the killing of Tyre Nichols.

“Don’t move,” followed by “Give me your hands” and “Lie flat, goddamnit,” were some of the conflicting commands barked by the five Memphis police officers who detained Nichols. “Defying” their orders was interpreted as a rebellion and as an unjust result. Force was used on Nichols despite bodycam footage showing no grounds for violence.

We need to stop extrapolating the study’s findings to deaths like Tyre Nichols’, which do not involve violence against police officers.

Police violence with minimal provocation is also apparent in the 2014 murder of Eric Garner who displayed no violent nature. Despite his nonviolent crime, Garner was placed in an illegal chokehold and arrested in an aggressive manner that turned fatal.

This is also apparent in the 1997 case of Abner Louima, who was arrested at a nightclub after a physical altercation with another partygoer. He was accused of allegedly “attacking a police officer” and resisting arrest, both of which were later proven false in court. He was beaten, strip-searched and raped with a broomstick before being dumped at Coney Island Hospital by police officers claiming to have found him partaking in “abnormal homosexual activity.”

Later in court, the officers involved admitted they did not feel threatened by Louima.

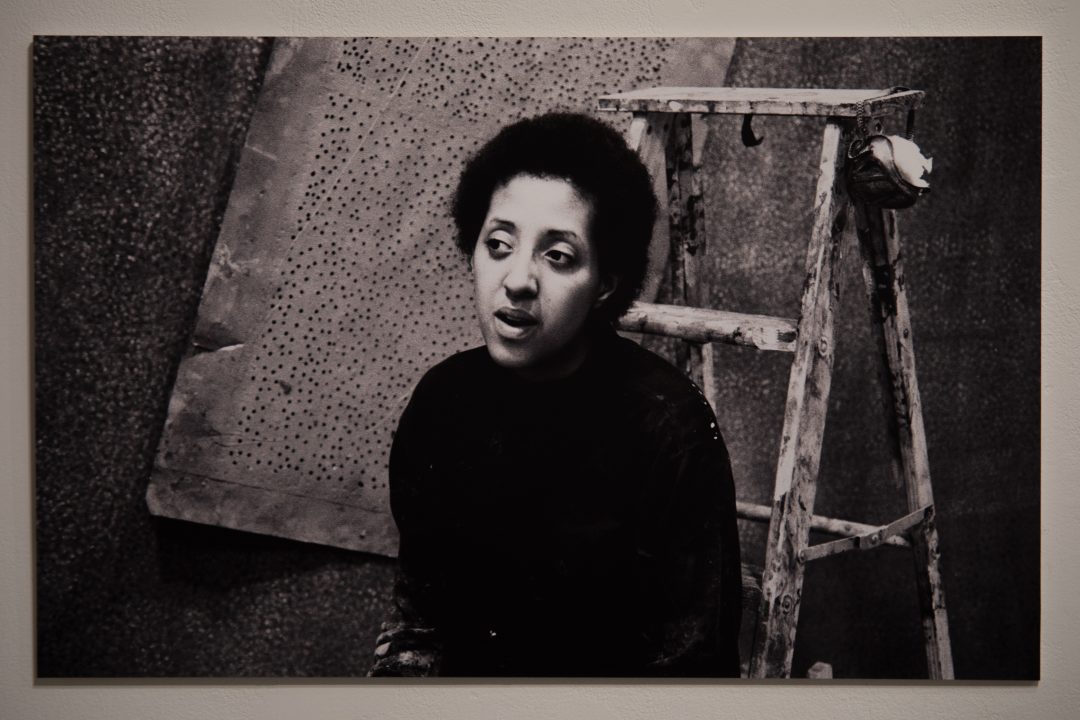

Despite the public’s introduction to Nichols in this tragic manner, we must not brand him solely as a victim. We must not brand any of those murdered at the hands of police only as victims. They were all individuals who led meaningful lives, accomplished goals, had hopes and dreams and left their marks on loved ones. Tyre Nichols was a father, an aspiring photographer and a son.

The way to honor his legacy is to appreciate his work, give his family time to grieve and spread awareness of police brutality so we will never have to hear another narrative of this injustice.

In order to avoid the harm the study perpetuated, the country needs education regarding police brutality, police culture, racism and privilege. Choosing to ignore the issue at hand and to not educate yourself on your own privilege makes you a contributor to the problem. Say his name and do not forget him: Tyre Nichols.

To further honor Tyre Nichols’ legacy, please visit his photography page.