On Sept. 28, Dr. Dong-Yeon Koh, an established art critic from South Korea, held a discussion in the Humanities building on her recently published academic book, “The Postmemory Generation in South Korea: Contemporary Korean Arts and Films on the Memories of the Korean War.” This book delves deeply into how the modern-day Korean society is remembering the tragedies of the Korean War through contemporary art and film.

Through this book, Koh combines art history and cultural theory while simultaneously moving away from the traditional monographic approach towards the categorization of artistic movements, such as modernism and minimalism, that is often embedded in Western art histories. Postmemory is a term coined by Marianne Hirsch that describes the responsibility of the next generation in bearing the personal, collective and cultural traumas of those before them.

Today’s generation has not lived through the Korean War but has learned of it through secondhand accounts. This led to newer generations being more apathetic and less antagonistic regarding their neighbors to the North. They’ve mainly consumed knowledge of the war from popular culture, such as through the film “Taegukgi: Brotherhood of War,” Koh explained. Each generation has their own version and perspective of the past, which results in a different idea of postwar Korea.

“[Through art and film,] this is how the historical past can continue to exist in the present through the efforts of postmemory generation artists,” Koh said. “Not in the way the past is authentically represented, but in how contemporary South Korean artists and filmmakers project, imagine, and forge the experience of their ancestors during the Korean War.”

This generational gap and “sense of distance” allowed the postwar artist’s crucial imaginary interpretation of the history in art and films rather than a strict responsibility for the historic truth, Koh explained.

The ending of the war threw the art world into a new era. Artists explored new ways of expression while simultaneously reflecting on the atrocities of the war. The new art movements, Korean Informel and Minjoong Misool, sprouted out of the desire to convey the political, emotional and cultural aftermath of the Korean war.

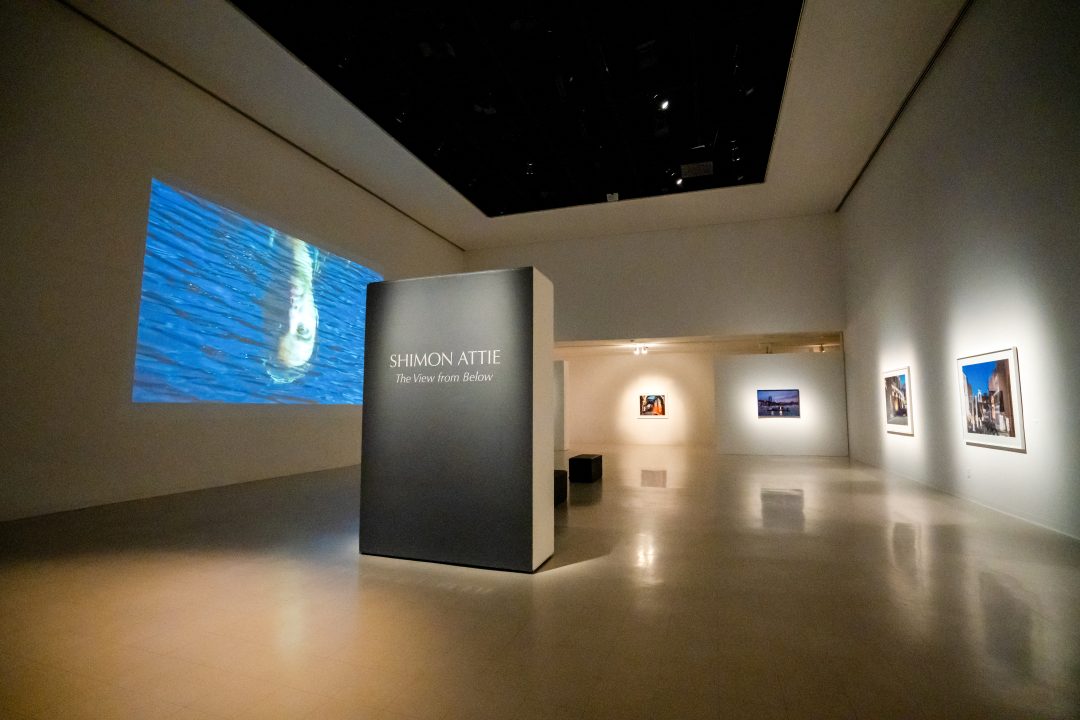

These artists began to take a more subtle and conceptual approach when portraying the violent memories of the Korean war as they became more “interested in the perspectives and processes through which particular information in history and politics becomes available or not in public,” Koh said.

While Koh believes it is not wise to generalize the Korean art scene of the 1970s and 1980s, she said the contrasting “abstract art of Informel and the realistic and socially critical art of Minjoong Misool, epitomized different ways of dealing with the Korean War and its continued legacy within postwar South Korean society during the 1980s until the early 1990s.”

Postmemory contemporary Korean artists and filmmakers explicitly reveal their confusion and ignorance towards the Korean War by refraining from the use of graphic violence the original images and replacing it with stronger narratives. In An Jungju’s contemporary dance video installation which interprets the pain of war victims, “Ten Single Shots,” the war sound effects were extracted from films.

“These media installations force audiences to witness how individuals with no direct memories of the Korean War can be emotionally and physically affected by the theatrical representation and reenactment of victims’ experiences,” Koh said.

Koh’s book attempts to weave diplomatic, political and militaristic histories in South Korea and people’s changing perceptions of the Cold War and North Korea with contemporary art criticism. Her book aims to “show [readers] how diverse and complicated contemporary South Korean’s ideas of the War and its national identity in the region.”