The state of Texas implemented a ban on abortions after a fetal heartbeat is detectable, which is normally about six weeks after conception, on Sept. 1.

This ban affects about 7 million people of reproductive-aged 15–49 — and most glaringly — Black and Hispanic women.

The “Texas Heartbeat Act,” backed by Republican Gov. Greg Abbott, was signed into law in May but took effect only now because of the Supreme Court’s refusal to intervene. According to the bill, unless deemed a medical emergency by a physician, people who perform abortions can be sued while those reporting them can receive monetary compensation.

One of the clearest flaws in the bill is that most women are unaware of any pregnancy by the time a fetal heartbeat can be discovered, which takes around six weeks; six weeks in terms of the menstrual cycle equates to only one missing period.

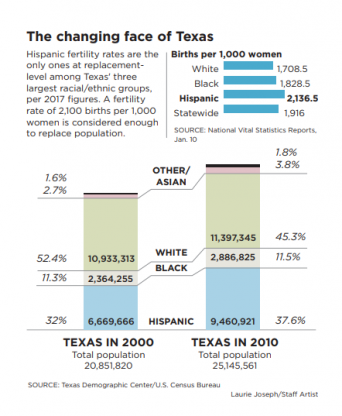

The population of Texas is 50% female and about 40% Hispanic or Latino and is home to about 5.5 million Hispanic women. According to the American Immigration Council, “one in six Texas residents is an immigrant.” With these statistics, it’s safe to infer that the people most at risk from this ban are women of color, as now under S.B. 8, “at least 80 percent of women seeking an abortion will no longer have access to care in Texas.” This bill is not an anomaly nor a surprise, it’s just the latest of attacks on the health of women of color.

That is not to mention the already lacking healthcare resources open to women in Texas. “Texas’ maternal mortality rate is above even the U.S. average, at 18.5 deaths per 100,000 live births” and disproportionately affects Black women who account for “11 percent of live births but 31 percent of maternal deaths.” According to America’s Health Rankings, Texas is crowned the “least healthy state” with “26.2%… of women ages 19-44” who are not insured, mostly affecting “Hispanic and non-Hispanic Black women.”

Executive Director Lupe Rodríguez of the National Latina Institute for Reproductive Justice wrote in Salon of these “baseless restrictions” that only add layers to barriers. “Texas has a ban on telehealth providing medication abortion care, a ban on most insurance covering abortion — which means Texans must pay out of pocket — and a parental consent law,” Rodríguez wrote. “They called a special session to ban abortion medications, one of the safest and least invasive ways of ending a pregnancy.”

Rodríguez is one of many activists fighting against these laws and mutations in other states. News of the endangerment of women’s health in Texas sparked outrage and debate all over social media and left many worried about the future of reproductive rights.

Under the cover of darkness, by choosing to do nothing, the Supreme Court allowed an unconstitutional abortion ban in Texas to go into effect last night.

Their decision doesn’t change the fact that reproductive rights are human rights. We'll fight for them.https://t.co/hp1N6G2S3M— Hillary Clinton (@HillaryClinton) September 1, 2021

In 2019, about 70 percent of abortions in Texas were provided to women of color. In 2020, it was found that about 2.3 million women earn less than the poverty threshold in Texas, and two out of 10 Hispanic or Black women experience poverty, a rate double that of white women. With the already pre-existing meager support of women’s health, these restrictive movements leave many women of color with very limited and dangerous options.

Associate Professor and Director of Undergraduate Studies at Stony Brook University Nancy Hiemstra, whose research focuses on how state policies shape patterns and consequences of human mobility with a focus on the restrictive border and immigration policies, spoke to The Statesman on the consequences the ban has on Black and Hispanic women.

“This is a state that has very little support for women in terms of state-supported prenatal care and also supports for women and children, and educational programs for children, and additional resources to support healthy development as children grow,” Hiemstra said. “It is essentially a law that will mean that a lot of women, with a greater impact on women of color, will essentially have no reproductive choices and be forced to have babies they may not feel that they can properly care for… They may not have the resources or access to resources to make sure that they’re healthy and receive all the things they would want a child to receive.”

Dwindling numbers of patients coming in for ultrasounds in women’s health clinics in Texas show the exact repercussions of the ban. Forced to flee seeking healthcare, states like Oklahoma and New Mexico are seeing an influx of patients who have traveled miles to seek help. But that is just for those who can make the trip. Professor Hiemstra says these trips, which are already a big financial burden, may be impossible for some women because of other factors such as fear of deportation.

“These laws also impact [immigrant] women in Texas, as Texas has some of the largest detention centers,” Hiemstra said. “They are holding the most families and women and children in ICE custody; we’re talking thousands, so all these people will have zero access to abortion. And also if women are undocumented in Texas, they do not want to risk crossing state lines, as that will immediately get them detained and deported. So this law does a lot to impact immigrants, many of whom are Latinas, meaning that they do not have access to this kind of healthcare.”

The battle for control over women’s bodies affects all women, but specifically in Texas, there are also connections to anti-immigration ideals. In a recent research article, Hiemstra analyzes contradicting U.S. policies pertaining to babies and abortion at the border.

“There are conflicts there, things that don’t match up. There can be the same people that are anti-immigrant and don’t want ‘anchor babies’ and don’t want women of color coming into the country, but they also don’t want to allow anyone to have an abortion.” Hiemstra said.

This bill will affect seven million Texas women of reproductive age, and many fear that number will grow because of the spread of this bill being introduced in other states. Just last week, Republican Florida state lawmaker Rep. Webster Barnaby introduced House Bill 167 that is modeled after the Texas Heartbeat Act.

These restrictive bans have been and will continue to be fought, as activists are not backing down. The Women’s Health Protection Act was recently passed by the U.S. House of Representatives, which is a direct response to the Texas ban.

One in four women across America have had an abortion. I am one of them.

Terminating my pregnancy was not an easy choice for me — but it was my choice. And it’s a choice every pregnant person deserves to make for themselves. pic.twitter.com/hpcEGNdlXd

— Rep. Pramila Jayapal (@RepJayapal) September 24, 2021

The bill passed 218-211 between parties, and brings to mind what exactly it is those backing the ban want to control exactly. With the restrictions on abortion, and no move to make progressive changes to women’s healthcare, the law speaks volumes of the concern for the safety of women of color.

As Hiemstra points out, “Keep in mind that it’s often the same people who support these laws who are against any type of birth control at all. They don’t want insurance to cover birth control, and they don’t want government money to be used for birth control, so it’s really controlling in that way, too.”

View this post on Instagram

On Oct. 2, the Women’s March led the Rally for Abortion Justice in Washington, D.C. along with over 620 events in all 50 states to support reproductive freedom.