A tremendous wave of anti-Asian racism following the coronavirus pandemic experienced in the last year has led to a global Twitter campaign, #NoSoyUnVirus, or #IAmNotaVirus, in which participants counter racism toward the Asian community.

Chinese Spanish activists Quan Zhou, Chenta Tsai and Jiajie Yu Yan joined Stony Brook University to discuss anti-Asian racism and Chinese diasporic identity in “Pensando Xībānyá: Voices from the Chinese Diaspora in Spain” on Feb. 17, one lecture in a three-part lseries.

The three artists and authors discussed cultural production, the #NoSoyUnVirus movement, and their experiences as creators during the heightened tensions of COVID-19.

The speakers were introduced by Moisés Hassan Bendahan, a doctoral candidate in Hispanic languages and literature at Stony Brook University, and moderated by Mary Kate Donovan, assistant professor of Spanish at Skidmore College. More than 130 guests attended the event, co-sponsored by Stony Brook University and Skidmore College, eager to gain new insights from the live Zoom webcast, which offered free admission, and a lively chat room where questions could be forwarded to the hosts and participants.

The conversation opened with an astute connection to the name of the lecture series — how each speaker related to the notion of diaspora, and what diaspora meant to this eclectic group of Chinese Spanish creators.

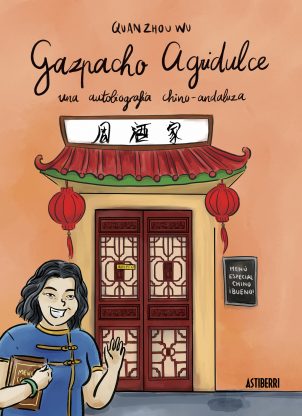

Quan Zhou is an author born in Algeciras, Andalucía whose experiences as a Spaniard of Chinese descent inspired her webcomic and graphic novel “Gazpacho Agridulce” and its sequel, “Andaluchinas por el mundo.” In 2020, her graphic essay “Gente de aquí, gente de allí” was published — exploring, with penetrating insight, prejudice, belonging, racial bias and what it means to be Spanish.

“In Spain they used to call us second generation immigrants, which is really bad because I immigrated from nowhere, I was born here. The second generation of immigrants started to feel very offended … it affects how you relate to people and how people perceive you,” Zhou explained, describing an experience that many Chinese Americans and other diaspora from all over the world may find familiar.

The perpetual foreigner syndrome is one where native citizens are perceived as foreign because they belong to minority groups, a form of nativism and xenophobia that has manifested in racist verbal and physical attacks against Asian Americans, especially as the world continues to wrestle with the COVID-19 pandemic.

“Is diaspora a good term? Maybe this is a better term for our parents who have a better relationship with our country of origin. The experience that makes who I am today is multicultural or bicultural … I was frustrated because I could not find any words to describe it, and they said maybe you should decide for yourself because you are not satisfied with the words for you from those older than you,” Zhou continued, alluding to the power of redefining oneself through creative work.

The work to understand one’s identity can be complex and indefinite, even during unremarkable times, and the uncertainty and crisis of the pandemic gives creativity a new urgency, in terms of self-preservation and anti-racism.

“When I was working on ‘Gente de aquí, gente de allí,’ when I write and when I draw it is for the girl I was 20 years ago, so that I do not feel lonely or lost. So that she understood what she was going through,” she said.

Chenta Tsai is an internationally recognized musical artist and performer known for their provocative stage name — Putochinomaricón — and challenging the genre boundaries of contemporary pop with witty lyrics critiquing gender and race in 21st century Spain. He also writes a regular column in El País, the largest national newspaper in Spain, and their first book, “Arroz tres delicias,” was published in 2019.

As the roundtable turned toward the topic of representation of Asian Spaniards in the media, Tsai spoke about the importance of maintaining non-hegemonic spaces for Asian Spaniards. In these spaces Asisan Spaniards should be allowed to produce art, separate from mainstream media’s frequently fickle interests in the Chinese diaspora shown most recently by the COVID-19 pandemic coverage.

“I notice a lot especially in the industry, in the people who are supposed to change … they proposed me to be the Chinese person eating bat soup on TV … they were going to stop coronavirus by going back in time, and stopping me from eating it. Are they interested in long term, or are they interested in the moment because this subject is touching many people?” Tsai said.

The speakers agreed that the normalization of Chinese diasporic representation in their native countries is an essential aspect of racial justice. This is especially true when it comes to combating isolation and stereotypes that lead to the “othering” mode of thought, which is often behind racial hate crimes.

“This conversation is a key element to change perspectives about China and immigration,” said Jiajie Yu Yan, a filmmaker born and raised in Barcelona, known for his short film “Xiao Xian,” the first Mandarin-language film nominated for a Goya Award. His sumptuously colored work has won awards at the Thailand International Film Destination Festival and has been screened at more than 40 international film festivals.

For many artists, being Chinese or Asian is not the end of their difficulties. Tsai also explained that finding artists of color who also identified as queer was a significant challenge. The notion that a queer artist of color could do lead a normal life was foreign to Tsai.

It was “growing up without anyone saying that you can do what is normal for Spaniards,” Zhou told Jiajie and Tsai.

“My parents said no one will hire you because you are Chinese, do you think a Spanish company will accept you? Luckily they were wrong, I published a book and was on TV, but no one told me it could be possible,” she said. “So we were jumping in an area where we were blind and in the dark. It would have meant a lot to me growing up if someone had said this was possible.”

While discussing the antiracist movement in Spain, the speakers elaborated on the benefits and drawbacks of looking at the history of similar movements in other countries such as the United States. Many acknowledged the widespread influence of American social movements such as Black Lives Matter and the Stonewall riots on cinema and entertainment in Spain.

“A lot of Spanish people were sharing the black square for Black Lives Matter, but thought that it was mainly in the United States,” Tsai said. “We have to acknowledge that these movements and discrimination also happen in Spain … it’s true that there has been also a lot of resistance in Spain that we also have to remember, because it is part of us and our history.”

The black square on social media was posted simply to make many people feel better about themselves according to Jiajie. But to him, black squares weren’t enough to represent the actual dangers many people experience.

Online spaces and virtuality were alluded to several times throughout the conversation as locations of convergence, creativity and violence through the speakers’ usage of social media for artistic promotion.

“You have a responsibility publishing content when it has a broad audience. The ‘Chinese Virus’ made legitimate these types of attacks so language is powerful … sometimes I have to log off with negative comments,” said Zhou, referring to President Trump’s usage of the epithet to refer to COVID-19, against the World Health Organization’s illness-naming guidelines, a decision that has incited racist attacks against Asian-appearing individuals.

Throughout the conversation, the concept of identity became even more complex and enriching, as the three Chinese Spaniard artists talked about negotiating between the values of diasporic homelands and countries of residence through artistic references. It can result in a delicate balance between cultures and individuals, high art and consumerist culture.

“In Taiwan, one of my wishes was to connect with my own roots — one of the fantasies Netflix is selling you to yourself — I am a POC going back to my roots to discover myself. I realized how hypocritical it was to say I wanted to connect to my roots in Taiwan because it didn’t connect with the Indigenous community,” Tsai told Zhou and Jiiajie. “When you talk about your roots you have to be careful, because we have to know our place in the community in Taiwan. There is trash culture, and bands, that are seen as something negative by Confucius because they are chaotic. The Rabbit is a folk tale that talks about gayness and queerness because the character is queer and they catch him once spying on the military and they beat him and he dies and he comes back as a rabbit, and people make a shrine for him. There is a temple in Taiwan for ‘Hu Tianbao,’ this story.”

Nonstop comments and questions from viewers streamed in, discussing everything from racial and LGBTQ+ allyship to the usefulness of writers and films such as W.E.B. Dubois, Angela Davis and the 2015 Mandarin-language film “Mountains May Depart” in understanding identity.

“I find this conversation extremely interesting. The concept of diaspora resonates differently in different historical contexts,” E.K. Tan, event collaborator and associate professor of comparative literature and cultural studies in the department of English and Asian American Studies wrote in the Zoom chat.

The speakers hope that their works will reach a wide audience.

“Our bodies are understood as political territories, and you are already making activism by walking down the street, or having afro hair, or embracing yourself. It is part of how I see and write music … So many people from different communities can connect … what connects is that otherness, and feeling like you don’t belong anywhere,” Tsai said.

His words are underscored by the virulence of anti-Chinese racism today, and the unsettling feeling that it has not left where Tsai sits, in his room with a six-hour difference from Stony Brook and across the Atlantic Ocean, untouched.

“I would like everyone to go to the movie to better understand the Chinese community in Spain,” Jiajie added. As the week of Lunar New Year draws to a close, the hope is that the engaging and provocative cultural productions of these three artists mend communities.

The “Pensando Xībānyá: Voices from the Chinese Diaspora in Spain” series continues this month on Zoom with the second event, “Writing and Diaspora,” on Mar. 24 at 1 p.m. and the third and final event, “Activism and Education,” on Apr. 14 at 1 p.m.